Timeline

- 1918 End of the First World War

- 1919 Treaty of Versailles

- 1921-40 Alliance with Poland

- 1923-25 Ruhr Crisis

- 1925 Locarno Pact

- 1928 Kellog-Briand Pact

- 1929 France begins to build the Maginot Line

- 1931 Great Depression hits France.

- 1932 Washington Conference

- 1934 Stavisky Affair, right-wing coup

- 1935 Reaction to the Saar

- 1935 Hoare-Laval Pact

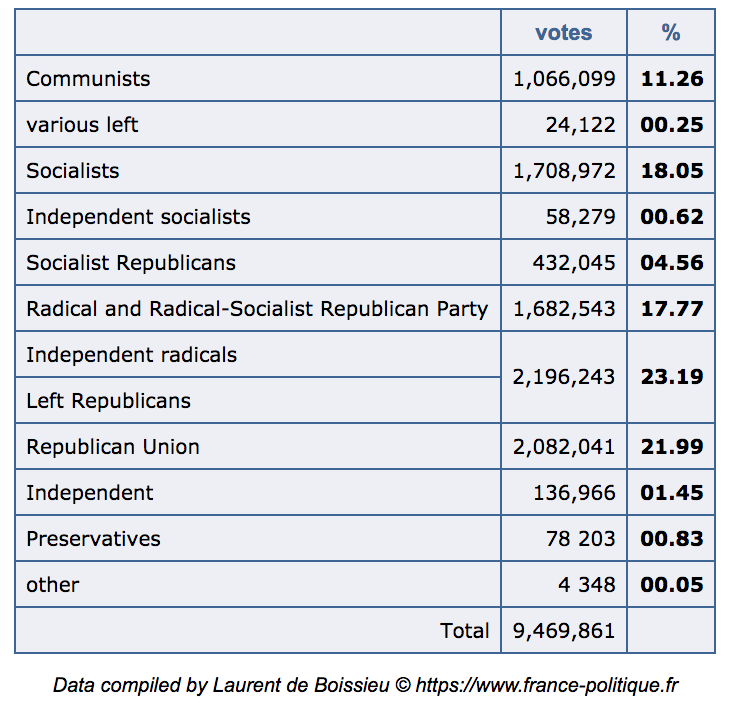

- 1936 Popular Front election victory, Leon Blum, Stresa Front, Reaction to the reoccupation of the Rhineland, Reaction to the Spanish Civil War, Appeasement, Matignon Agreements, Gold Standard abandoned.

- 1939 France goes to war against Germany. The government outlaws the Communist Party.

- 1940 Germany successfully invaded France, bypassing the Maginot Line.

- 1940 Northern France became Nazi-occupied but the southern half became Vichy France.

Costs of the First World War

France in the 1920s

by Jon Jacobson, Strategies of French Foreign Policy after World War I

- France demanded extreme reparations from Germany, arguably they became the main barrier to European peace because of this. At Versailles, the French initially wanted a world fund to help restore the battlegrounds of the First World War. When this was rejected, France was ‘forced’ to ask for large reparations from Germany. See Treaty of Versailles page for more detail.

- On the other hand, France may have been correct in their demands – Germany may have exaggerated their ability to pay and this argument continues to this day. Moreover, their demands may have been the solution to peace in Europe.

- French policies after the war were too ambitious, they did not have the money or resources to achieve them. Their only asset for leverage was the Treaty of Versailles, asking the USA and UK to help enforce it. This did help the French policy of limiting German power.

- In general, France was quite weak after WWI ended, despite the victory of 1918. They had three main policies afterwards: security from renewed aggression, reparations to prevent a German resurgence and to build global markets. All failed by 1924, especially with Germany becoming a major player again in 1924 (Dawes Plan, also League of Nations in 1926). Furthermore, the country did not make good use of the German reparations. It did not produce a much-needed industrial base and therefore eventually had to rely on German trade for coal. It also continued to rely on US and UK money, and therefore influence, so had to accept the Dawes Plan.

- Owing to France’s lack of coal, they made deals with Germany (Seydoux Plan 1920-21). However, as Germany had little leverage, France usually had the better terms. However, as the 1920s progressed, and Germany’s position improved, this began to change (1925 Locarno Pact is a good example).

- The Ruhr invasion (1923-25) was months in the making, the French government (Poincare) resisted pressure from within for months but finally, after all diplomatic channels were exhausted, decided to act. The aim was to get leverage against Germany to ensure the reparations were paid. It succeeded in that it made Germany eventually back down.

- Arguably, it was also an attempt to show French power, especially to the UK and US. Ironically, French action may have forced the hand of the US in trying to solve the reparations issue (Dawes Plan), and in doing so made Germany stronger (they could build their own economy as the burden of annual reparations payments became staggered). Consequently, the Ruhr Crisis was a failure for France. It damaged the reputation of France internationally particularly with the two countries they sought strong relationships with, Britain and the United States.

- The demilitarisation of the Rhineland was a long-term aim for France. After WWI, the French government wanted more, the separation of this area from Germany. However, Britain did not agree and France considered their entente with her more important than this desire. This was especially true after the US refused to be part of the League of Nations or guarantee French security in Europe.

- French policy wavered during the 1920s, from requesting German cooperation to meet the demands of Versailles, to using force to occupy the industrially prosperous Ruhr and Rhineland regions. Government departments, including the army, differed on what the key policy should be. One option was to weaken Germany by encouraging greater federalism in the country. However, this failed.

- The reparation payments from Germany were issued as bonds (guarantees of payment). However, they only maintained their value if the German currency was stable. Therefore, the invasion of the Ruhr, aimed at ensuring payments, indirectly made them lose value.

- To meet the needs of French industry, they wanted the coal mines of the Saar to be ceded to France permanently, overriding the planned plebiscite of 1935. However, this policy was dropped because they knew there would be opposition from London, Washington and obviously Berlin.

- Jacobson explains that some historians blamed Poincare’s weak leadership for the failure of 1920s policy. Furthermore, by invading the Ruhr one can argue that he either wanted a simple financial settlement or a more ambitious political solution to the reparations issue (US, UK and France dictating to Germany the limits to their power).

- However, if Poincare reached a settlement with Germany over reparations, this may lead to a future relationship between the two countries. One country who did not want this was Great Britain. Therefore, they encouraged the Dawes Plan which would limit France’s involvement in finding a solution.

- French successes during this decade were that Germany continued to disarm, the British troops continued to occupy the Rhineland and the Dawes Plan gave France much needed finance.

- French defeats were the end of the Treaty of Versailles, it was being revised by as early as 1924. The Dawes Plan did not take security into account at all. This took leverage away from France. Moreover, it made Germany recover and begin to be a threat to their own security. And it made gave political power to the US and Great Britain, the French idea of being the dominant power in Europe will have to wait!

France, money problems, prosperity and De Gaulle

To what extent was the invasion of the Ruhr a success or failure?

What should France’s foreign policy be in the 1930s?

Task

- For each country, summarise the decade of the 1920s. Explain the consequences of the First World War and how it fared politically, economically and militarily.

- Then explain what French policy should be towards that country and give reasons why.

a. Germany

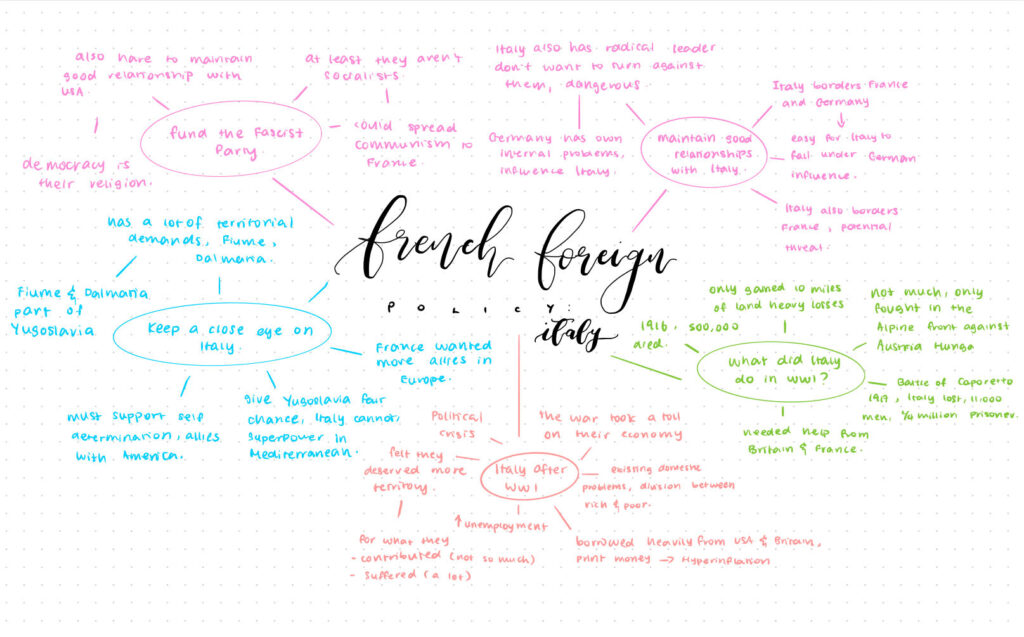

b. Italy

c. Britain

d. Poland

e. Czechoslovakia

f. Hungary

g. Russia

h. Yugoslavia

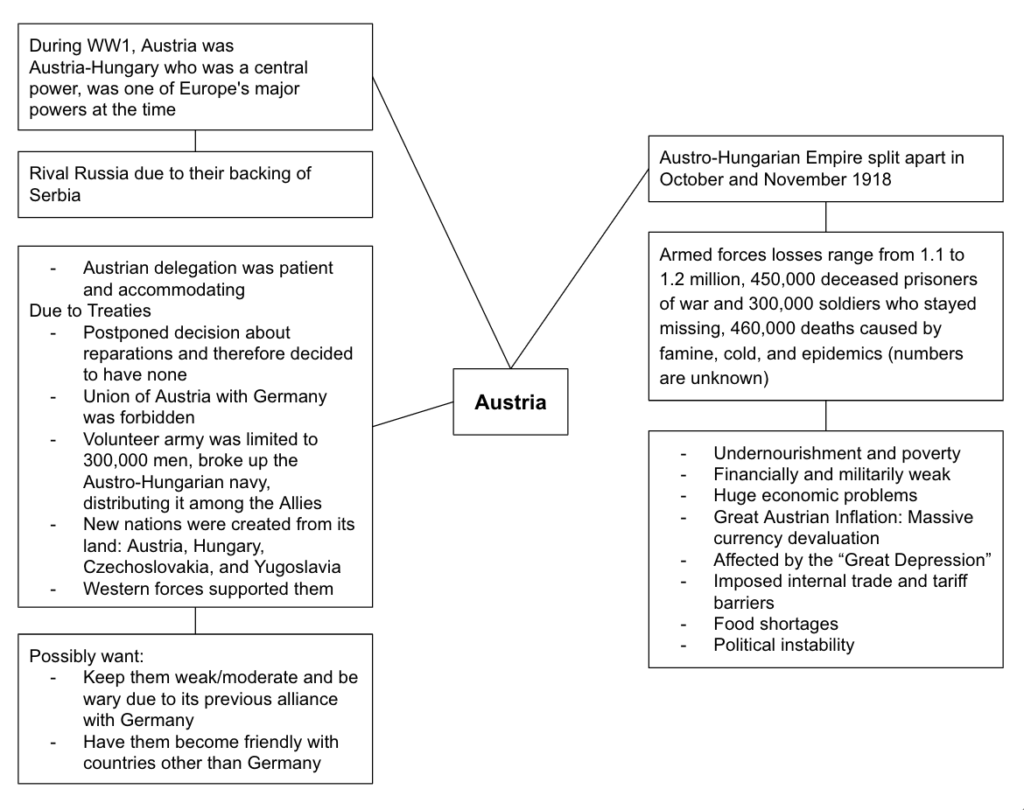

I. Austria

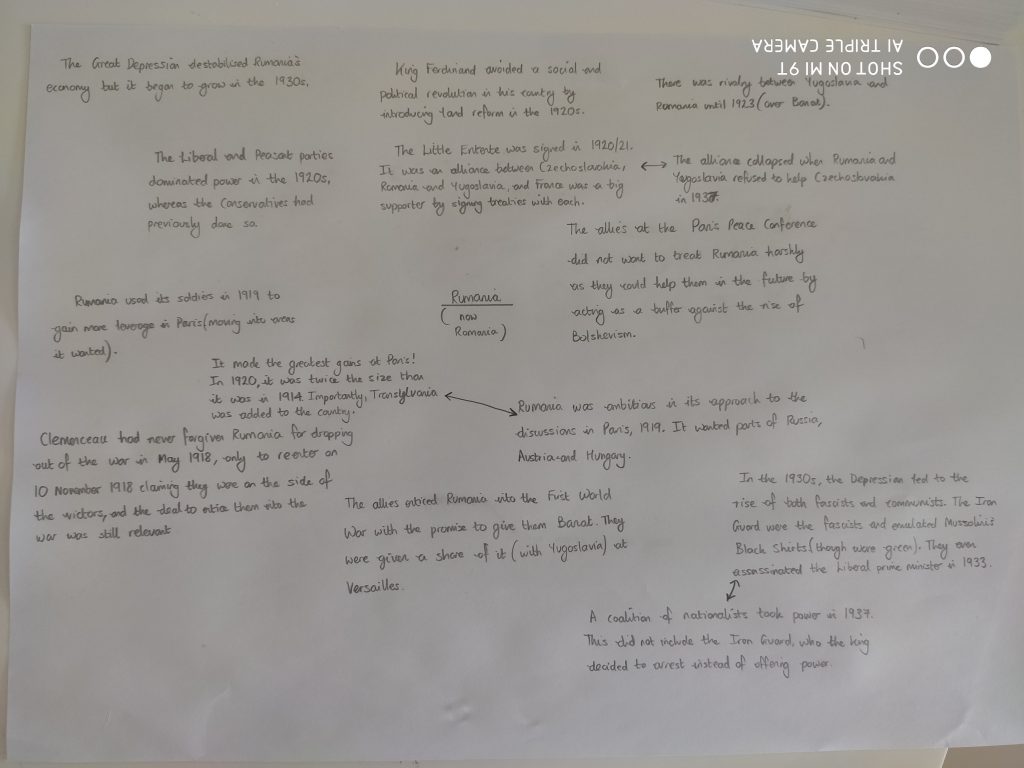

j. Rumania

French foreign policy during the 1930s towards Rumania would be friendly because of the possible threats to its own security, largely Germany but also the Soviet Union.

Social and Economic Issues

- Declining population, largely caused by the male deaths in the war (17% of the male population). This birth rate would also influence government thinking for security, the German population was much higher. Furthermore, three million soldiers who survived were traumatised or injured. This would create various problems for the government, how would they care for them? With regards to the population, contraceptives and abortion were banned, and there were medals for fertility.

- The loss of life or incapacity would affect economic production for the decade.

- Women still did not have the vote in the 1920s or 1930s (they achieved suffrage in 1944!). Their rights largely came from the Napoleonic Code of 1804, and successive governments did not want to change this for fear of women voting for Church parties. They did not have the rights to open a bank account or own property until 1965.

- However, women found new opportunities for work during the war and many wanted to continue afterwards. In 1921, 42% of adult women were still employed.

- There were deep class divisions in French society, the elite had a great deal of power. Those at the top of the social hierarchy (the grande bourgeoisie) had passed through private schools (the lycee) and university, opportunities unavailable to the majority of the population. Therefore, the working class did not benefit from economic growth, the 1914 wages only returning in 1929.

- There was full employment during the 1920s. France allowed immigration to make up for the losses in manpower because of the war (1.5 million people, mainly from Spain, Portugal and Italy).

- France suffered high inflation during the mid-1920s although recovered for the latter half of the century. The second point is important, not everything was in decline during the interwar period. The French economy was growing faster than its competitors in the early 1920s and by 1929, the low value of the franc had increased exports and improved trade. However, people who had savings were hit hard (the franc was worth one-tenth of pre-war value during the 1920s).

- Alsace-Lorraine was taken back by France in 1919, adding 1.7 million to the population. However, independence movements began because some wanted autonomy from Paris. But the government suppressed their efforts.

- The German Army had destroyed French resources when occupying them during the war. For example, the coal mines were flooded. This would take a huge amount of time and money to rectify.

- The financial cost of the war was paid for by borrowing, selling off gold and war bonds, and printing money. When the war ended, these had severe consequences for the country: runaway inflation and debt owed to much of the middle-class population. The costs of repaying loans (mainly to the USA and UK) presented problems to respective governments. However, their alliance with Russia and the consequent loans given before the October Revolution would never be returned. Lenin argued it was not he who had borrowed.

- France was reliant on German reparations to solve some of their economic problems. That Germany did not pay brought further political and economic issues for the country.

- When the Left came to power in 1924, the wealthy were fearful of industries being nationalised so took their money out of the country. This is capital flight and reduced the funds the government could spend on the country.

- France’s recovery was reliant on large industries. One, in particular, was Andre Citroen’s motor industry, copying Henry Ford’s assembly line.

- There were improvements in agriculture (mechanisation and infrastructure) and some farmers benefitted from the increased food prices. But in general, too many small farmers produced too little and so did not prosper.

- American culture influenced France during this time, jazz became popular. Whereas the US had the Roaring Twenties, the French had ‘les annees folles’ or the crazy years.

- Paris became a centre for literature, art and the surrealist movement began here (the latter was perhaps a response to the war, its founder, Andre Breton, had worked in a psychiatric hospital during the war).

- Writers such as James Joyce and Ernest Hemmingway visited Paris.

- Charles Lindbergh flew the first solo transatlantic flight in 1927, landing in Paris.

- French cinema was hugely popular in the 1920s and 1930s.

- Chuch attendance decreased during the 1920s although the policies to increase the birth rate found favour with the Vatican.

Political Issues

- France expanded its empire with the mandates over Syria and Lebanon.

- The Treaty of Versailles, as mentioned earlier, was both a success and failure. Clemenceau wanted far more reparations for Germany and to break the country.

- There was instability in the French government, there were too many parties to achieve a stable consensus. Moreover, the economic problems (mainly inflation) faced were difficult to overcome. Between 1919 and 1940, France had forty different governments and twenty prime ministers! Furthermore, because there would only be a general election every four years, many new governments were appointed by the president in a coalition, so did not have a mandate from the people to govern.

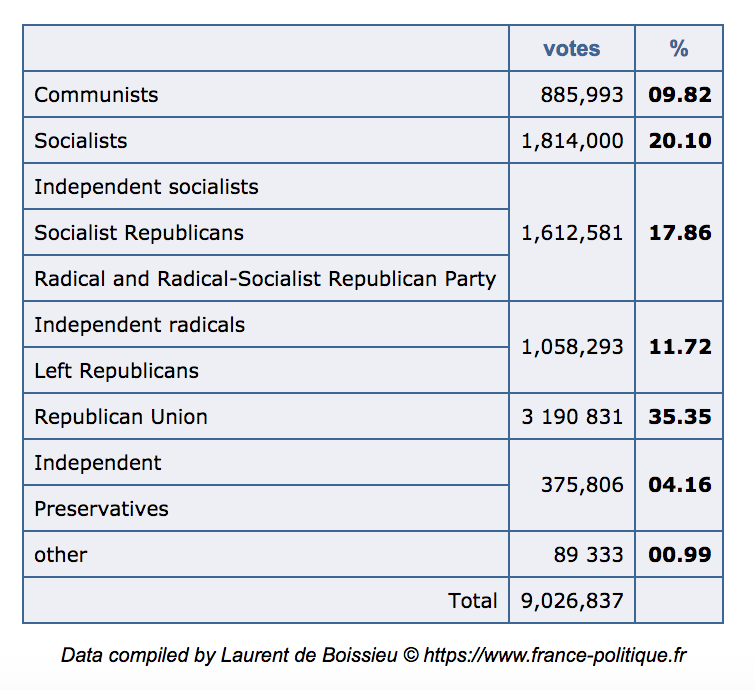

- The growth of the French Communist Party was also an issue. The Socialists and Communists were rivals so the vote for the Left was split (the Communists split from the Socialist Party in 1920). This made it more difficult to reach a consensus within governments.

- The Right saw the rise of Mussolini in Italy and international popularity he received. This gave them hope that France could emulate the Fascists.

- The major political group was the Radical Party. It believed in the sovereignty of parliament, the separation of church and state, universal suffrage for men and a laissez-faire policy. Arguably, it was conservative too, believing in the ideals of the French Revolution.

- The Radical and Socialist parties had similar social policies so most passed into law. But they would not join into a coalition together (although were in government between 1924-26), believing they could have a majority of their own.

- On the other hand, there was the emergence of fascist groups, trying to emulate Mussolini (Action Francaise and Croix de Feu). But they only became prominent in the 1930s.

- The Bloc National (centre-right) were generally in power during the 1920s (perhaps many French people were fearful of a similar Bolshevik Revolution). Poincare was in charge until 1924 when the Ruhr debacle led to the people ousting him for the centre-left Cartel des Gauches (included Radical Party). However, the Cartel could not solve the problems of inflation and so Poincare returned in 1926. He took unpopular decisions such as raising taxes and reducing government spending. This led to economic stability and three years of ‘prosperity’.

- The Left, or Cartel de Gauche, was only in power for two years (1924-26). The prime minister, Eduard Herriot, complained that he was up against a ‘Wall of Money‘ so was unable to pass the legislation required. The financiers and industrialists prevented him from enacting the policies of the Left. (Wileman, p. 487).

- However, the historian Jean-Noel Jeannene argues that the Cartel was financially incompetent and should not blame the ‘Wall of Money’. It had failed to address the economic problems and it was left to the Right to solve them in 1926.

- Donald Wileman argues that the Cartel was doomed from the start. 1924 saw the introduction of a bizarre voting system (which did not last long afterwards) meaning that the coalition did not have the power or the votes to pass their legislation. He also defends the Cartel, agreeing with Herriot’s excuse above, and stating that France always faces the same barriers to social and economic progress.

- Alsace and Lorraine were ‘returned’ to France and it began imposing French culture and language on the two regions.

- French foreign policy focused on Germany and security. Aristide Briand was a key figure, serving as prime minister eleven times and foreign minister on several occasions. He signed the Locarno Pact in 1925 (respecting borders) and the Kellogg-Briand in 1928 (outlawing war), winning the Nobel Peace prize in 1926 (he won it jointly with Gustav Stresemann).

- Furthermore, France committed to alliances with eastern European countries (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia) to ensure Germany could not attack again.

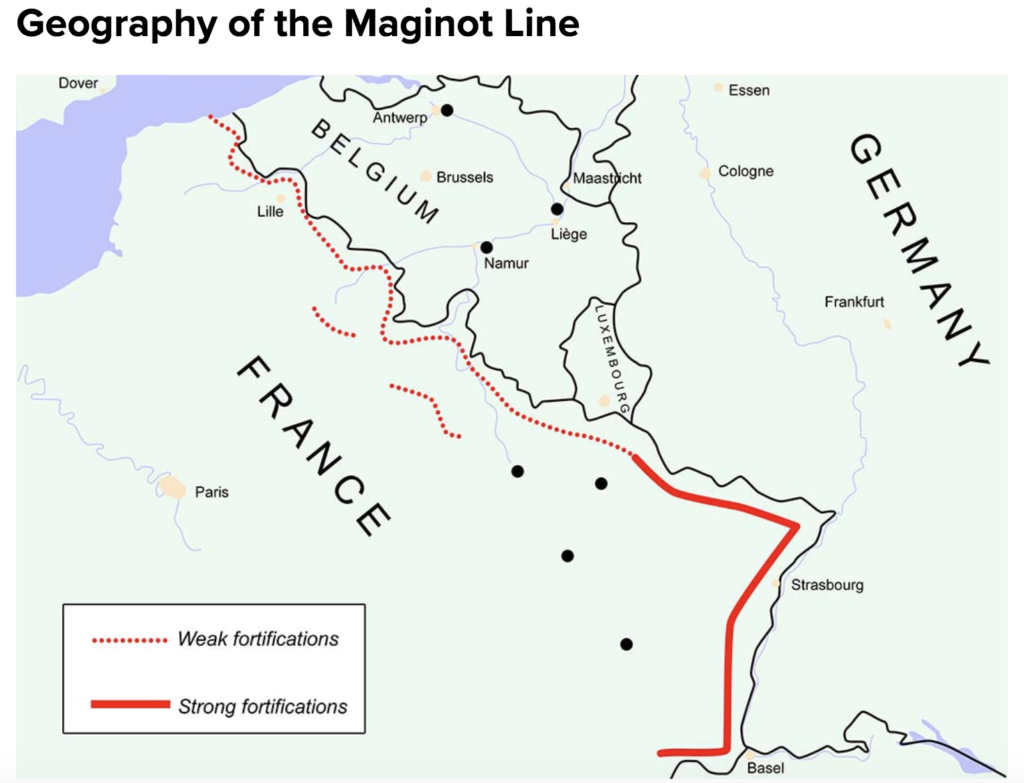

- Lastly, the government decided to build the Maginot Line in 1929, devoting one-third of its budget to the defence of the country. It also maintained the largest army in Europe after 1925. The Maginot Line had an impact on the psyche of the military and the country. It thought defensively rather than offensively. Military thought focused on what to do if Germany attacked, not planning on taking the initiative to win the war.

- At the time, reputable military thinkers such as Basil Liddell-Hart advised the British prime minister Chamberlain that both the Maginot and Siegfried Lines were impenetrable. (R. Self, Biography, p. 395) The French psyche of remaining on the defensive was clearly affecting the British government too.

France in the 1930s

Foreign Policies

- The French government strived to develop or maintain alliances with Eastern European countries, in the hope of deterring a future German invasion.

- France was neutral for much of the decade, preferring to stay out of the Spanish Civil War (Non-intervention Pact, 1937), acquiescing towards Italy with the Hoare-Laval Pact (in the hope Mussolini would not strengthen his relationship with Hitler – although he did in 1936 with the Rome-Berlin Axis) and accepting the German reacquisition of the Rhineland in 1936 (Britain refused to use force too and France could not do so alone).

- In 1928, France decided to build the Maginot Line, a defensive structure from Switzerland to the North Sea. However, Belgium refused to cooperate because of its perception of French weakness and desire not to antagonise Germany in the future, so the Line was only strong up to the French/ Belgian border. Furthermore, Mussolini also saw this weakness and opted to side with Hitler rather than France, even though he had reservations over Germany’s relationship with Italy’s rival, Austria.

- The joint British/French policy of appeasement was implemented from 1936 to 1939. It culminated in the Munich Conference of 1938, whereby the Sudetenland was ceded to Germany from Czechoslovakia. It was hoped this would prevent war although Hitler went back on his promise to leave Germany alone in March 1939, ending the appeasement policy.

How Britain and France saw Appeasement

Social and Economic Issues

- The Great Depression did not hit France until 1931. Exports declined and this affected both the industrial production of the country and food prices. This greatly affected the political issues facing France, western governments struggled to find solutions to the global crisis through diplomatic means.

- In the first half of 1931, there were 40 000 unemployed each month – remember that there was full employment in the 1920s. Although the figure for France was lower than many others, it did not take into account one million immigrants who returned home or who moved back to the countryside.

- Agriculture suffered hugely because of oversupply, prices dropped significantly as a result and consequently, incomes for farmers did too.

- The Depression in France lasted longer than in other countries, the political instability one of the reasons why. Moreover, the decision to maintain the franc on the gold standard (not leaving it until 1936) did not allow the government to devalue in order to increase exports (this was maintained to control inflation, a huge concern of the 1920s).

- France’s share of international trade plummeted by 44% by 1935, the government attempted to increase their exports to colonies but this did not make up for the shortfall.

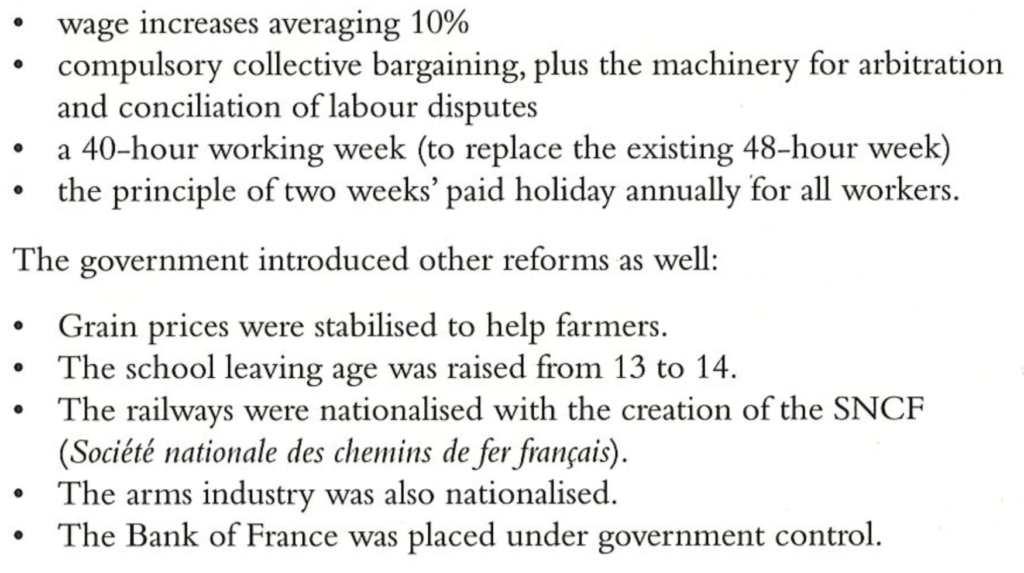

- The Popular Front’s victory in 1936 introduced the Matignon Agreements (after two million workers went on strike demanding the new government enact more extreme policies). These were designed to stop the national strikes and to reform the economy. They included a wage increase of 10%, a forty-hour working week and annual holidays for workers and for industry, armaments, rail and the Bank of France were put under government control. These policies (agreed by employers) were initially popular but gradually led to a worsening economy – companies raised prices to accommodate the increased wages and productivity fell because of the reduced working week.

Political Issues

- As with other countries, governments found it difficult to deal with the economic problems caused by the Depression so France was politically unstable. It faced problems from the Right (the 1930s saw the growth of the right and Fascism. The Action Francaise, Croix de Feu (former soldiers) and Jeunesse Patriotes were a constant threat to the stability of the government especially as they saw the success of Mussolini, Franco and Hitler.

- The Stavisky Affair led to further criticisms of the government for corruption and anti-semitism. It was enough to bring the government down and led to Edouard Daladier (Radical Party) becoming the leader.

- But in 1934, there was a right-wing coup which used the Stavisky Affair as evidence that parliamentary democracy and the government were failing. It failed with huge demonstrations from the Left and the moderates supporting the Republic, and the police killing seventeen in the riots which also took place.

- Who supported the Right? As in other European nations, these nationalist groups were funded by wealthy donors. The middle class also supported them (because their savings suffered due to inflation), preferring their ideologies than the socialists or even the Republic itself. People who opposed the Bolsheviks tended to support the Right and those who were anti-Semitic or xenophobic. As many immigrants came into the country too (from Italy and Spain – escaping their authoritarian regimes, Poland and Jews, many from Russia who had escaped the Russian Civil War and the rule of the Bolsheviks).

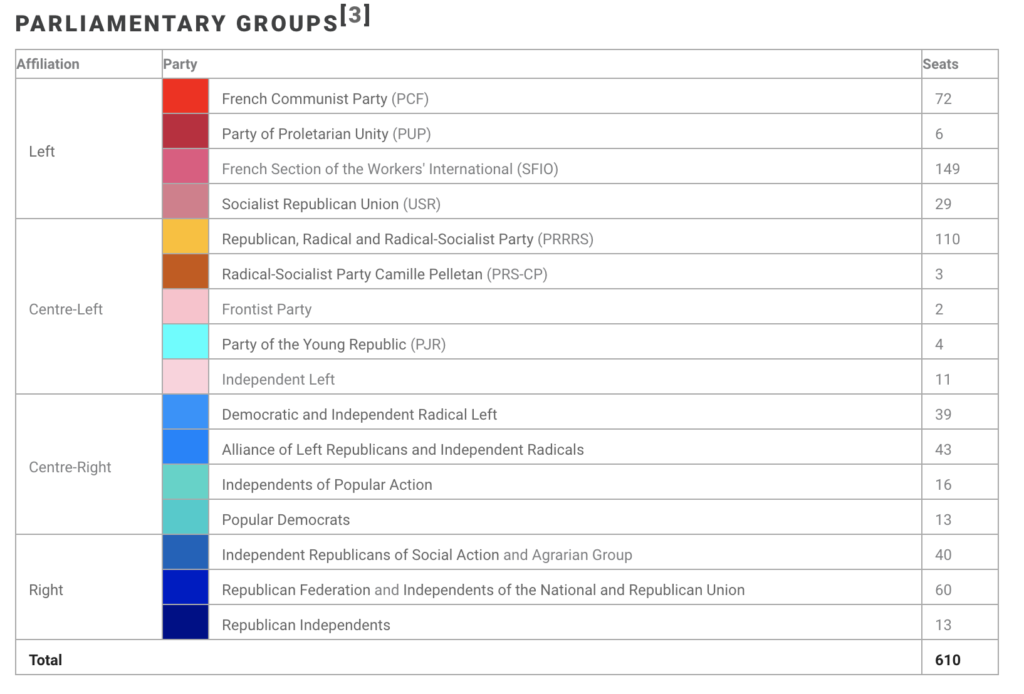

- In 1935, the Left responded to the increasing support for the Right with the formation of the Popular Front, with the Communists, Socialists, and Radicals all under one umbrella. The Left had been frightened by the coup and decided they had to act. It was elected in 1936 and introduced sweeping social reforms.

- However, it could not solve the economic problems as it promised to and had several prime ministers between 1936 and 1940.

- As evidence of political instability, they had eight different governments between 1932 and 1934. They tried to reduce public spending and raise taxes but this did not help solve the problems of the country. For example, by reducing public spending it decreased demand so prices became lower – profits affected – unemployment and/or wages reduced.

- In response to the 1936 general strike, where two million workers occupied factories, the Matignon Agreements were passed. They were welcomed by the working class and lower-middle-class but not so for business leaders and the right. Inflation was caused by the wage increased and production fell because of the reduced working week.

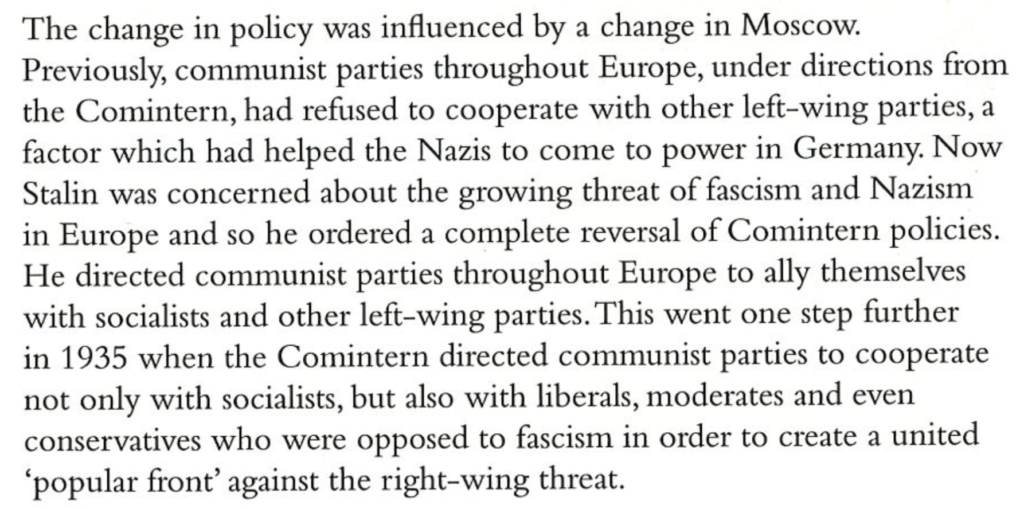

- As a result of fascists gaining power in Europe, Stalin and Comintern directed communists to ally with other socialists and left-supporting parties (see a response in the image below). In France, this led to the formation of the Popular Front. The parties were unified in stopping the right and had campaigned on policies such as a shorter working day, government controls for prices, more benefits to workers, more support for the League of Nations and disarmament, and changing the tax system, but had differences in how they were to govern. However, when Leon Blum achieved power, the communists refused to work with him as part of the government but he also refused to work with them.

French Popular Front Gov’t, 1936-38, top to bottom: Socialist Minister of Air Marcel Déat, Communist leader Maurice Thorez, and Socialist Prime Minister André Léon Blum.

- One of the problems for Blum was that he was Jewish – therefore difficult for the Right to support him, and he was bourgeois – so the Communists may not support him either. As they had 330 000 members by 1936, they had considerable influence politically in France and particularly in Paris.

- This worsened when Blum refused to offer Republicans in the Spanish Civil War any aid. He wanted to act but the Radicals in his coalition and the British government persuaded him not to. In doing so, he lost support from socialists and communists, and the eventual breakup of the Popular Front.

- Blum resigned in 1937 as he opted to strengthen the economy at the expense of social reform. He tried to appease French businesspeople and prevent capital flight. As a result, he lost the support of the Left in the Popular Front. When he sought to rule by decree, an authoritarian measure, the growing number of opponents refused and he was asked to step down. Even though returning in 1938, the Popular Front was weakened.

- The weaknesses and instability in the country may have led to the defeat of France during the Second World War. It was invaded in June 1940 and its much-praised pre-war armed forces were easily defeated. Had the country been more unified, especially over the economy, things may have gone differently.

Note: France was similar to Spain in its political problems during the 1930s. It could have led to civil war but there are important differences that kept the country ‘peaceful’ during this time. Firstly, there was the absence of a monarch who had just abdicated – there was no power vacuum to be filled. Secondly, there was little appetite for conflict in France because of the memories of 1914-18.

Perspectives

The Right wanted more secure borders, especially in the Rhineland.

John Merriman argues that the Popular Front failed because of three reasons – the three parties could not agree with one another. Two examples, Leon Blum was Jewish and bourgeois, and the Communist Party would not allow any of its members to serve in the 1936 cabinet so that absolve themselves from blame if the government failed.

Secondly, the industrial owners did not comply with the Popular Front’s policies. They were not consulted, they would cost money, and so were ignored. And finally, Blum’s decision to not help the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War was unpopular. Despite public clamour to help in the war, Blum explained that the British and US advised him not to internationalise the conflict, fearing another European war.

Historiography

Robert Paxton – Successive governments did not want to increase taxes (until 1926) because they would lack political support. This stopped France paying off its war expenses so economic problems continued. These had a huge influence on foreign policy – France should not go to war again!

The Popular Front victory was not a swing to the left for the country but rather indicated a politically divisive society which favoured the most united coalition in elections. But Paxton defends the government as they were the first to recognise leisure (the annual two-week holiday) as a basic social need. He blames Blum’s compromising position, appeasing both the right and left, as the reason the Popular Front failed.

William Shirer – Although the wealthy are not immune from blame for the country’s economic problems, he criticises the Left for their lack of reality. They were in power in 1924 with a large majority (so able to pass most legislation) but did little to change the economy. They preferred to avoid confrontation and this weakness led to further instability.

The Popular Front’s election victory in 1936 only worsened divisions in the country. Part of the reason was that Leon Blum was a Jewish, leading to a wave of antisemitism. The fact that he was a socialist also concerned conservatives too.

Roger Price – the French politicians did not want to devalue the franc because it would affect the reputation and global standing of the country, and lead to opposition from people with savings. This prevented French goods from being able to compete on the global stage because other countries had devalued.

Martin Roberts – The Popular Front failed because of foreign threats. Hitler’s Nazi Germany was gaining in power and there were fascist opponents in both Spain and Italy to deal with. Furthermore, the conservatives and wealthy of France were fearful of a communist takeover. Supporting nationalists was one of their solutions, the phrase ‘Better Hitler than Blum’ was one used at the time.

Further Reading

Wileman, Donald G., What the Market Will Bear: The French Cartel Elections of 1924, Journal of Contemporary History , July 1994, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 483-500