Rise to Power

- Mussolini was a nationalist and a socialist. He was editor of the socialist newspaper, Avanti, before he was expelled from the party for supporting Italian involvement in the First World War. Although he became a fascist, he was still a socialist and the Fascist manifesto reflected this, e.g. to introduce a mininum wage, reduce the retirement age and to improve workers’ rights.

First World War

The following documentary is useful when putting Mussolini’s rise to power in context. It discusses the consequences of the First World War om European countries and how the conditions led to changes to the ‘Old World’. It is recommended you watch it all although if just for Mussolini, begin from 12.15.

After the First World War, new governments spread across Europe. From Republican democracies to Communist to Fascism. Italy was the first to swing to the latter.

- Italy joined the First World War in 1915 but there was not a huge amount of popular support for doing so. She was promised land in the Treaty of London by Britain, France and Russia.

- It suffered a series of defeats, the most notable being the Battle of Caporetto. There were 300 000 prisoners and 350 000 deserters.

- The military and political leadership got the blame for these defeats. One of the government’s placatory responses was to offer the vote to all adult men. However, one of the downsides of proportional representation (also in Germany) was that extreme minorities could have a voice. Another was that it was difficult to maintain a stable government because of coalitions.

- Mussolini used these conditions to make himself leader and dispose of the liberal democracy.

Khan Academy – Mussolini Becomes PM

Versus History – The Rise of Mussolini

Historiography

According to Nicholas Burgess Farrell, fascism had mass support by 1922.

But Benedetto Croce argues that the fascists maintained their position in Italy because of the fear of the postwar economic crisis and of communism.

Denis Mack Smith argues that

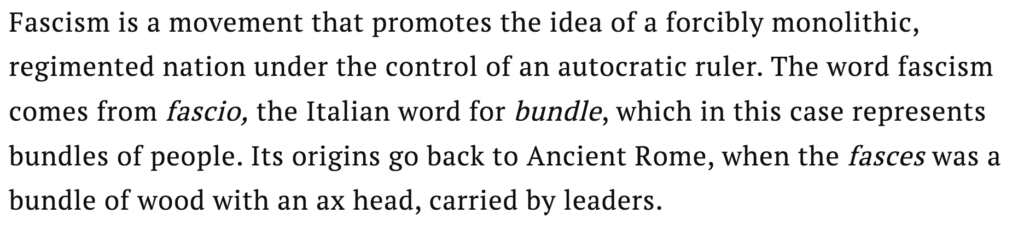

What is Fascism?

Fascism is a concept far too easily used to describe politicians and governments. It is imperative that you read and understand the meaning so can accurately label the authoritarian leaders of the twentieth century. There are several articles online which you can read to help you understand fascism.

Umberto Eco: A Practical Guide for Identifying Fascists

Terry Eagleton’s What is Fascism argues that the concept is primarily used by governments to maintain the purest form of capitalism. It is also a strategy to keep the proletariat weak and the bourgeoisie strong. Fascists take advantage of an economic and/or political crisis and install an ambiguous ideological government. In the twentieth century, the latter involved the threat from the Left. If you argue Spain, Italy, Germany and Japan were fascist, the threat from the Soviet Union was used to help them become so. (My words) Eagleton explains that industries become monopolies in which they have a huge stake. Consequently, they can create a totalitarian state as a result, controlling all aspects of society. Free trade is restricted to protect these monopolies and, when the economy declines as a consequence, imperialist expansion becomes the next stage.

However, fascism is more than an economic policy. Politically, the country becomes more nationalistic and minorities are persecuted or scapegoated. Eagleton uses the example of Polish metal workers in Nazi Germany to prove this. Rather than keep these highly-skilled tradesmen for the economy, they were exterminated.

Modern History Sourcebook: Benito Mussolini: What is Fascism, 1932

Further Resources

Consolidation of Power 1922-26/29

Mussolini was similar to Hitler in that he was given power, he did not seize it. But he was asked by the King to become Prime Minister. By 1928, he had removed the King’s right to do this and became Il Duce, the ‘Leader’.

1922 March on Rome, Emergency Powers

1923 MVSN established, Acerbo Law

1924 Corfu Incident, Fiume annexed, Aventine Succession, Matteotti Murder, creation of the Ceka, Press censorship and the banning meetings of opposition parties.

1925 Mussolini declares himself dictator. Battle for Grain, Vidoni Pact

1926 Mussolini has the power to pass decrees without parliament, Rocco Law passed, Battle for Land and Lira takes place

1927 Battle for Births

1929 Lateran States, Concordat

- Mussolini took advantage of the King’s request, assuming the senior role in the relationship as a result.

- From the beginning, Mussolini was effective at putting himself into key positions being Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior and Minister of Foreign Affairs. Among many things, this helped him come through the Matteotti Crisis (see below).

- But he had only 35 fascist deputies out of 535. He needed to rely on political support if he was to hang on to power.

- In November 1922, Mussolini was given emergency powers. Even the deputies who doubted how he gained his position voted for him because they thought he was capable of stopping left-wing anarchy.

- There were various nationalist and fascist groups (ras, squadristi, Arditi) in Italy when Mussolini took power. He knew he was only the leader of Italy because of the violence they threatened and used. Consequently, to continue with their support (and to prevent them from fighting each other) he created the Fascist Militia or MVSN in January 1923. 300 000 men were now paid by the government and members who were too unruly were expelled.

- Mussolini believed he needed a personal bodyguard so in 1924 created the Ceka (modelled in the Russian Cheka).

- In 1923, he managed to get the Acerbo Law passed. This gave him two-thirds of the deputies in the parliament as the law promised any party which had over 25% and won the election would receive this allocation.

- He ensured he had control over his own party by creating the Fascist Grand Council. Important members were part of this group but it was Mussolini who had the final say.

- The murder of Matteotti, a Socialist politician, curtailed Mussolini’s power for a time. De Felici (see historiography) wrote that he was not innocent. However, instead of denying any involvement, he went on the attack. Mussolini took responsibility for the murder as the Fascist leader and challenged anybody to prosecute him. As the opposition was too weak, none did so. Mussolini now knew he could rule without them.

- The 1924 Aventine Succession was a challenge from the Socialists, Liberals and Communists to Mussolini’s power. They walked out of the Italian parliament and set up their own government, the intention to force King Emmanuel III to remove Mussolini and accept them as rulers of the country. However, the monarch was fearful of the instability and possible violence it would cause and remained loyal to Mussolini. Furthermore, the absence of these opposition politicians from parliament only helped him pass laws and win any votes of no-confidence in him.

- Although Mussolini was pragmatic in his ambitions in the early years of his rule, he did take some aggressive action. Corfu and Fiume were contested, the latter becoming part of Italy in 1924. The dispute over Corfu resulted in Greece paying Italy 50 million lire in reparations. Both resulted in Mussolini gaining in prestige and power.

- Mussolini knew that economic problems brought him to power so therefore they could also remove him. With the Rocco Law (1926), he forbade strikes to take place and had spent the years 1922 to 1925 curbing the power of the trade unions. The Fascists had more of a corporatist strategy to the Italian economy – the industrialists played a key role in it.

- The south of the country was underdeveloped but in the control of landowners. As Mussolini had control of the government resources, these people gave him the support (in return they would be awarded government contracts and even power via the Fascist Party in the future) he needed to control that part of the country.

- In 1925, Mussolini declared himself a dictator (to lead in times of emergency).

- The Papal States (the name given to land previously owned by the Roman Catholic Church in Italy) had lost all its land in the 1870 unification of Italy. As a result of the Lateral States, the Roman Catholic Church received £30 million in compensation in 1929 and the Church was given 109 acres in Rome to create a new papal state – the Vatican. The pope was allowed a small army, police force, post office and rail station. History Learning

- The 1929 Concordat (not to be confused with Hitler’s) made the Roman Catholic Church the state religion. This further removed the religious opposition to Mussolini.

Khan Academy – Mussolini to Dictator

One could argue that Mussolini began as a revolutionary. However, once he took power he soon changed, appeasing the conservatives (Church and landowners) rather than instigating political change.

But Il Duce was not a dictator because…

- The Army swore an oath to the King, not Mussolini

- The elections were rigged so figures of 98% support were far from accurate.

- He still had to deal with parliament until 1939.

- The 1929 Lateral States was evidence of the leverage the Catholic Church had, he had to buy them off. Furthermore, they continued to have a role in Italian society, unlike Hitler’s Germany.

- Civil servants working for the government were not all Fascists, the government did not sack everybody who was not as they were needed to run the country.

- Some judges had to be imprisoned because they punished Fascists.

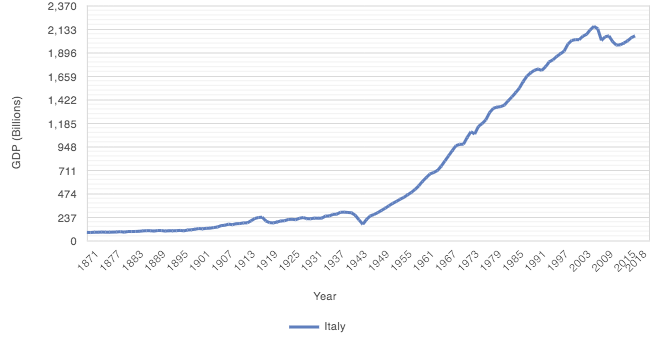

The Economy under Mussolini

Although this topic is important to Unit 14 – Interwar Years, it also helps you understand how Mussolini consolidated his power.

Do you think this video shows you an accurate portrayal of the Italian economy? Think about OPVL when answering this.

- The Italian economy suffered because of the First World War, leading to debt quadrupling, inflation at 560% and unemployment reaching two million. This was in contrast to the decade before the war when the economy prospered.

- In the second half of 1922, the global economy grew and this helped Italy too. Taxes for foreign investment were cut and trade agreements were negotiated. However, the finance minister who helped to achieve this was sacked because he grew in popularity (De Stefani).

- From 1926 Mussolini knew that he had dictatorial powers to make changes to the country and to the economy. He neutralised the trade unions (the Vidoni Palace Pact meant that there was only one trade union, the Fascists’), introduced the Rocco Law to make strikes illegal and gave power to industries who would manage the workers for the country – corporatism. Wages, conditions, hours of work, productivity, benefits and reasons for dismissal would be decided by the corporate body.

- It was successful to the outside world (via propaganda) but it led to huge bureaucracy and annoyed the workers who had less freedom to negotiate pay and work conditions.

- Between 1926 and 1934 real wages slumped by at least 50%. To counter it, the government introduced Dopolauoro. This was a programme to create cheap and accessible leisure activities.

- Mussolini continued to use rhetoric to maintain support for his policies. He used the term’Battles’ to promote new economic policies: Battle for the Lira (1926-38), Battle for Grain (1925-39) and the Battle for Land (1926-1938).

- Battle for the Lira – the lira was revalued to increase its strength, a strong country has a strong currency. This was successful in terms of reducing inflation but failed because it raised unemployment. It aimed to force Italians to buy Italian-made products since their export markets were reduced because of the revaluation. However, the country was too underdeveloped to do so, it was still largely agricultural. This turned about to be an advantage when the Great Depression hit, they did not have to rely on export markets as much as the industrial powers.

- Battle for Grain – High tariffs were placed on food imports and people were given financial incentives to cultivate land and grants given to buying machinery. However, export crops (olive oil) collapsed and the South of the country suffered through soil erosion. Many of the poorer farmers suffered too.

- Battle for Land – Marshland was to be cleared and reclaim any that could be used for agriculture. War veterans benefitted from this policy as they were allocated some of the 80 000 hectares which were made available. Moreover, two new towns (Saubadia and Latina) were showcased to demonstrate Italian achievement. However, only 5% of the land the government said was available actually was and the land was generally infertile.

- The Great Depression hit Italy in 1931. Major banks collapsed (Bank of Milan) as did major foreign creditors in their economy. Moreover, over 1.3 million were unemployed by January 1932.

- But the finance minister, Antonio Mosconi, created the Sofindit (October 1931) and the IMI (November 1931), which stabilised the economy and made credit avaiÌable.

- Furthermore, Alberto Beneduce took charge of the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction (lRI) and it gained control of large heavy industries in Italy as a solution to the economic crisis. It had some success in comparison to other states.

- Finally, it also organised the building of rail and road, power stations and even deluxe liners to alleviate the unemployment situation.

- 1936 changed things. Mussolini and the Fascists no longer advocated economic stability as their imperialist ambitions took over. The war in Abyssinia destabilised the lira and the rearmament costs (costing one-third of government spending) led to increased taxes being levied on the country.

- Italian aid in the Spanish Civil War also depleted Italian coffers leading to industrialists and financiers to criticise the government.

- The Pact of Steel was signed in 1939 and Mussolini was advised not to go through with his obligations by the finance minister Revel.

Economic Leadership Secrets of Benito Mussolini

Socialist Economics of Italian Fascism

Perspectives

Marxists could argue that Mussolini exploited the proletariat and gave financial power to powerful industrialists via its corporatist strategy.

De Felicianists could argue that Mussolini put Italy on the world stage with the same strategy. Moreover, the work of the IRI made significant improvements during the Depression.

Further Resources

Kahoot – Consolidation of Power

Maintenance of Power

Economy

See Consolidation of Power above.

1936 – Italy came off the gold standard, this was later than most.

Foreign Policy

This section should be studied for the Move to Global War too.

1923 Corfu invaded and Italy receive fifty million lire in compensation.

1924 Yugoslavia gives Fiume to Italy via the Treaty of Rome, recognises the USSR as a country.

1925 Locarno Pact signed, confirming Europe’s borders

1926 Treaty with Spain and de Rivera

1928 Italian & Ethiopian Treaty of Friendship

1933 Four-Power Pact signed (Germany, Italy, Britain & France). Italy also signed

1935 Stresa Front signed, reaffirming Locarno

1935-37 Abyssinia invaded in 1935 with 500 000 Italian troops.

1936 Mussolini no longer objects to the Anschluss, Abyssinia taken, Rome-Berlin Axis.

1936-39 Spanish Civil War

1937 Italy joins the Anti-Comintern Pact & withdraws from the League

1939 Mussolini invades Albania, Pact of Steel signed with Germany.

1940-44 Second World War, Italy joins in 1940 by attacking Egypt from its colony of Libya.

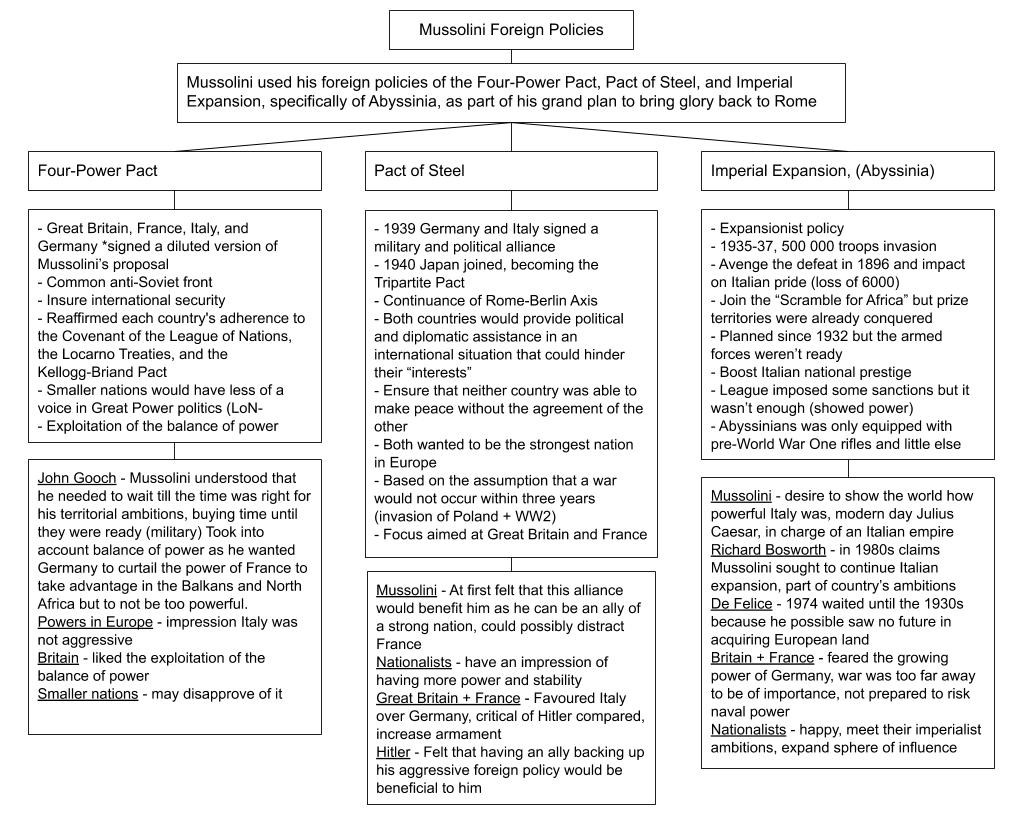

Explanation of Mussolini’s Foreign Policies

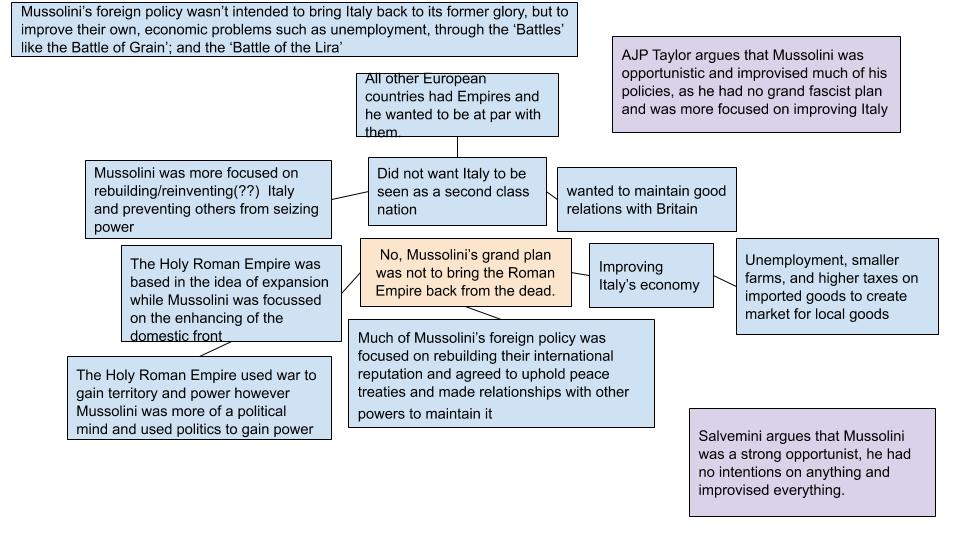

- Mussolini’s foreign policy in the 1920s was aimed at restoring Italy’s international reputation. He agreed to uphold the post-war peace treaties to get respect from Europe’s governments. However, it was also practical for Mussolini to focus on the domestic political and economic problems of Italy instead of beginning an aggressive foreign policy.

- Italy’s improved status would then allow her to re-negotiate the lands she thought she should have been given at the Treaty of Versailles (see Treaty of London 1915 at the top of the page).

- Italy’s rivals were Austria, France and newly-formed Yugoslavia (the latter two in particular as Mussolini despised them both. In turn, they developed a strong relationship to keep Italy in check. Ironically, Germany’s increasing military power from 1933 brought France, Yugoslavia and Italy closer together). He also hated the League of Nations, feeling that it was had no power.

- John Gooch argues that Mussolini had territorial ambitions but they were on hold until the time was right, he wanted a strong Germany to curtail the power of France and then take advantage in the Balkans and North Africa. However, he did not want Germany to be too powerful so instigated the Four-Power Pact in 1933. This would further the impression that Italy was not aggressive and mean that German rearmament was increased slowly. However, the four powers could not agree and it failed.

- Mussolini’s attack on Abyssinia was mainly driven to avenge Italy’s defeat in 1896. He had been planning this since 1932 but the armed forces were not yet ready. He was prepared in 1934 because he knew Abyssinia was building up her army so had to act quickly, Britain would not act to stop him, and that France supported his actions because they feared the growing power of Germany.

- The war ended in 1936 with a victory but his use of poison gas disgusted the Europeans. However, the garrisoning of troops limited Italian military power in the Second World War.

- In the same year, Mussolini agreed to aid the nationalists in the Spanish Civil War. He acted because he despised the communists and growing Soviet influence in Europe, he sought a growing influence in the Mediterranean with Spanish help when they were successful, and he realised that Italian contributions would strengthen the political relationship with Germany.

- However, Mussolini thought the Spanish Civil War would be short. Unfortunately for him, the war took three years and cost Italy both financially and militarily. One benefit was that his armed forces gained much-needed experience to fight future wars.

- The Rome-Berlin Axis and Anti-Comintern Pact were signed in 1936 too. These broke the relations Italy had with Britain and France.

- The Anchluss of 1938 would have been a problem for Italy in the past as it strengthened Germany and could have been a major threat to Italy. However, Mussolini supported it due to his growing political, economic and military relationship with Germany.

- The Pact of Steel was signed in 1939. Mussolini wanted Japan to join but it did not want to commit to viewing Britain and France as enemies, it agreed to the USSR, however. Therefore, only Italy and Germany signed this alliance.

- Mussolini was encouraged by the Pact but was aware that Germany may take too much territory, including the Balkans (which he had wanted), but was acquiesced when he met Hermann Goering.

- John Gooch – Mussolini had sought war to further Italian ambitions for years and finally joined the Second World War in June 1940. However, his military commanders warned him that they were not ready. This would prove a costly error as the Italians were easily defeated in North Africa.

Women

Taken from Women under Italian Fascism by Alexander de Grand.

- Women played an important role in the Battle for Births and Land. The former was key to Italy’s future according to the Fascists. Mussolini – ‘Work, where it is not a direct impediment, distracts from conception’. The Fascists awarded gold medals to ‘producers’ of many children as an example of their belief in the importance of higher birth rates. As an incentive to men too, fathers with many children were more likely to get employment.

- Women who practised birth control were threatened with various consequences and education for it was also banned by the Rocco Code of 1927.

- As society became more conservative, the role of women became more traditional. Consequently, they were not politically active and this could be seen as a success for the Fascist regime. Some middle-class women became advocates of suffrage before the war and were optimistic afterwards. Unfortunately for them, they did not achieve women’s suffrage until 1945, although in 1925 Mussolini did allow them to vote in local elections.

- However, as some women took part in the resistance during the Second World War, it is hard to judge how successful the Fascist government was in this.

- One of the reasons to drive the policy of women and conservatism is that they would stay at home and reduce unemployment. In 1881, over 40% of women were employed. This declined to 26.5% in 1921 and 18.5% in 1931, the Fascists were successful but it could be argued the change was cultural too. Many emigrated to the US (making up 60% of Italian immigrants) and veterans from the war had more influence when demanding jobs after the war.

- Before the Fascists came to power in 1922, their constitution was influenced by the Futurists. Consequently, one of the rules was to allow women full voting rights and permitted to hold high office. However, after they took power the issue of women’s rights was forgotten.

- As the regime became a dictatorship as a result of the Acerbo Law of 1924, a writer commented that both sexes were now equal – they were both disenfranchised.

- Under Mussolini, female teachers were discouraged and they were prevented from joining the civil service. However, women continued to dominate the schools for younger children and the medical profession. Some were also able to join higher status positions such as lawyers, architects, and engineers, although numbers were not high. As the country embarked on war in the 1930s, ironically more women passed out from teacher training colleges than men.

- There was an attempt to merge feminism and fascism by Elsa Goss, the director of La Chiosa of Genoa in 1926. However, political magazines aiming to forward women’s rights were discouraged and La Chiosa became a fashion publication instead. One criticism against women and politics is that it was a factor in the declining birth rate.

- The Lateran States deal of 1929 further limited the role of women. The Catholic Church sought to preserve the family institution and consequently, their partnership with Mussolini’s government strengthened this view in Italy.

- The official position of women’s publications was that the Fascists did more for women than any previous liberal regime.

Perspectives

Opportunist

Intentionalist

Structuralist

Student Arguments

Cult of Personality

- De Felice said Mussolini had a genius for propaganda. However, one could argue that the strength of Mussolini’s cult was that it was not the state who published it, the population produced their own such was their devotion to Il Duce.

- It was a tool to keep the Fascists in check and force them to regularly speak highly of their leader.

- It was also a system to organise the population. With its focus on Mussolini as the perfect warrior and hero, he would serve as a role model for others and prepare them for war.

- His speeches were rehearsed to ensure the maximum effect. They were very effective because he worked tirelessly. Memories of them would last for years afterwards.

- When visiting a town, Mussolini would deliver a speech, inspect a factory and speak to the people individually and in groups. Importantly, they were photographed and filmed for a wider audience.

- As religion was very much part of Italian society, Mussolini tried to make himself a saviour or saintly figure.

- Schools had textbooks written by the state, the curriculum developed to be politically friendly to the Fascists and teachers ‘supervised’ to ensure it was delivered correctly. Students were also encouraged to take part in paramilitary groups which would further the ideological support for fascism.

- Many letters were sent to Mussolini from children although Paola Bernasconi argues that they could have been as classroom tasks by Fascist-supporting teachers.

- However, Mussolini did not create a population which followed his ideology absolutely although this may have been because of the failure of some of his economic and foreign policies, not the failure of his cult of personality.

Luck

- Mussolini achieved power because of several decisions made by other people – Italy joining the First World War (he supported it but it was not his decision to make).

- The Soviet Union and its communist ideology scared the middle and upper classes across the world. They were more likely to support nationalist groups, even if they were violent if they opposed any rise in socialism or communism.

Historiography

- In 1932, anti-Fascist historian Gaetano Salvemini argued that Mussolini’s foreign policy as opportunistic showmanship without an ideological agenda. In 1951, he went further explaining that he ‘was always an irresponsible improviser, half madman, half criminal, gifted only – but to the highest degree – in the arts of ‘propaganda’ and mystification.’

- In 1948, Georg Zachariae, one of Mussolini’s doctors, published a book which defended him. He argued that Mussolini stood up to Hitler’s racist ideological policies (although passed anti-Semitic policies himself).

- In the 1980s, Richard Bosworth claimed that Mussolini sought to continue Italian expansion but that it was part of the country’s ambitions (Abyssinia 1896, Libya 1911-12). Bosworth subscribed to the structuralist theory of history, Mussolini was not the great man who was taking Italy forward, they were going together. He even argues that the decision to go to war in 1940 would have been taken without the dictator as the leader, due to the country’s belief in Risorgimento.

- However, the key historian in the debate about how Mussolini conducted his foreign policy was De Felice (a revisionist theory of the 1980s). His conclusions are similar to Bosworth although argued them several years earlier in 1974. De Felice had an excellent reputation in Italy but his conclusions led to criticism that he was a fascist and supported Mussolini. The ensuing debate is similar to the Fischer controversy in Germany. However, De Felice did explain that the dictator was not aggressive in the 1920s, he waited until the 1930s (Abyssinia 1935, Spanish Civil War 1936-39, Rome-Berlin Axis 1936) possibly because he saw no future in acquiring European land.

- However, in his 2002 book, Mussolini, Bosworth added that the dictator could manipulate most people and kept power by doing so. Furthermore, he was much less in control of his country than Hitler was in Germany. Italian people ignored his protestations of totalitarianism.

- AJP Taylor and Denis Mack Smith, two prominent British post-Second World War historians, argued that Mussolini agreed with Salvemini in that Mussolini was opportunistic and his foreign policies were improvised. In fact, Smith argues that Mussolini only signed the Rome-Berlin Axis to deter western rivals, he did not aspire to any grand fascist plan. Moreover, he only went to war in 1940 when he realised he could not reach an agreement with Britain and France and maintain his alliance with Germany.

- But Stephen Corrado Azzi argues that the 1960s and 1970s (new documents had been available by the Italian government) saw a change from this perspective, Mussolini conducted foreign policy as part of a great plan – imperialism in Africa and expansion in the Mediterranean. For example, Alan Cassey in 1970 argued that the aggressive 1930s policies were begun in the 1920s, Fiume and Corfu. However, Mussolini did not go further because his foreign policy advisors kept him in check.

- Azzi concludes by explaining Mussolini’s foreign policy was a combination of his plans and opportunism. Italy was not strong enough to influence Europe but did have territorial ambitions because of their history. But by arguing Mussolini was merely an opportunist is to judge every other statesman this way too. None can completely take control of international events.

- Finally, John Gooch (see his lecture above) argues that Mussolini was thinking of using force in the 1920s far more than he did (against France and Yugoslavia). One of his key aims was to keep France and Germany separate, this failed when the Locarno Pact was signed under Stresemann. But Mussolini was hopeful that Germany would return to war in the 1930s to rectify the problems of Versailles and the First World War. He would buy time by appearing friendly and conciliatory towards the Europeans and then take advantage of the situation himself. In this, he disagrees with Denis Mack Smith and AJP Taylor but agrees with Azzi and arguably Bosworth.

Further Resources