Rise to Power

Historians and Hitler since 1945 – Tasks

Marxist historians may argue that Hitler became Chancellor because he had the support of the middle and upper classes.

Intentionalists may argue that Hitler’s plans to abolish the Treaty of Versailles and restore the military enabled him to come to power.

Functionalists would argue that German society brought him to power because of the problems (especially economic) they faced.

German Conservative historians may argue that the people had had enough of the liberal forces which had changed Europe since the French Revolution and preferred a more traditional, authoritarian leader.

You can also argue whether the reasons for Hitler’s rise to power was economic, political, military or social.

Studies after the Second World War ended focused on the fanatic that was Hitler. By the 1960s, reason overruled emotion and more objective studies were being published. Most historians subscribe to the functionalist or structuralist theory where German society was at fault for installing Hitler as the leader. Nationalist supporters in Germany, then and possibly even now would subscribe to the Great Man theory (Ian Kershaw uses ‘superman’) – it was inevitable he would take power because of his charisma, political ability, and foresight (this is the intentionalist argument).

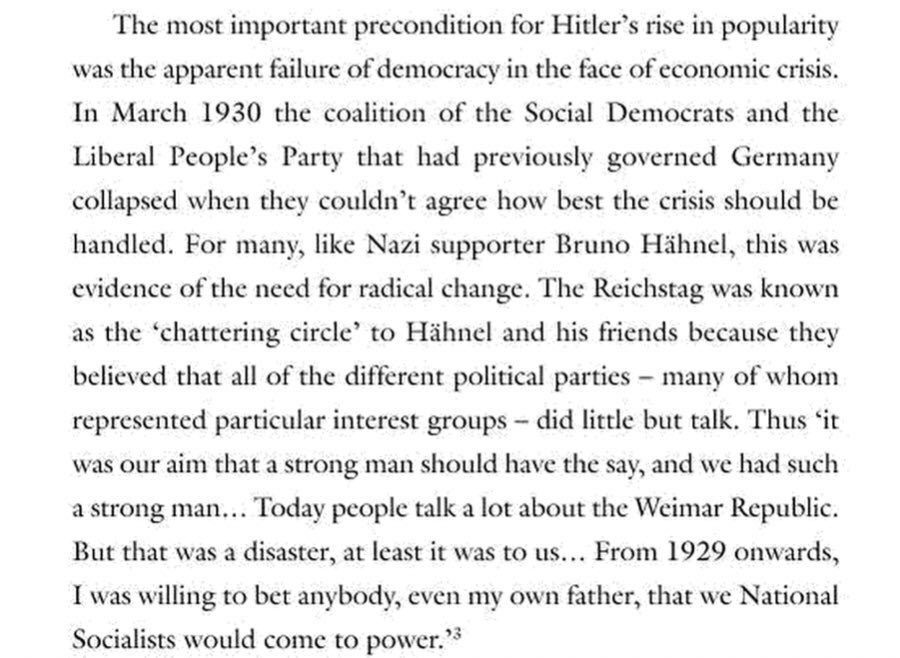

In the 1960s, William Shirer wrote in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich that Hitler inevitably rose to power within Germany. The rising nationalism and desire for authoritarian rulers from the late-19th century led to Hitler taking power in 1933. Shirer had lived in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s.

William Shirer is part of the Sonderweg school of thought, that it was inevitable that Germany would choose a leader like Hitler. This is closer to the functionalist theory, Hitler rose to power because of a combination of ‘German nationalism, authoritarianism, and militarism.’

Fritz Fischer (also useful to research for the causation of the First World War) believed that the German society was aristocratic and never fully subscribed to the foreign version of democracy. This was also the Sonderweg theory – glorifying the military, obedience to rulers and pride (or arrogance) in German culture. Evidence for this is Hitler being given a light sentence for the Munich Putsch, the appointment by Hindenburg as Chancellor in 1933, and given support from other right-wing parties. However, the evidence against this theory is that Hitler was not respected by the Junkers as he was merely the Bohemian Corporal (he was a low-ranking soldier in the First World War) and opposition continued to come from the army.

One of AJP Taylor‘s most famous quotes reflects his own functionalist view: “it was no more a mistake for the German people to end up with Hitler than it is an accident when a river flows into the sea.”

In the 1970s, revisionist historians such as David Irving in Hitler’s War argued that Hitler had been treated badly by history. He was a product in German society who demanded an authoritarian leader to solve their problems.

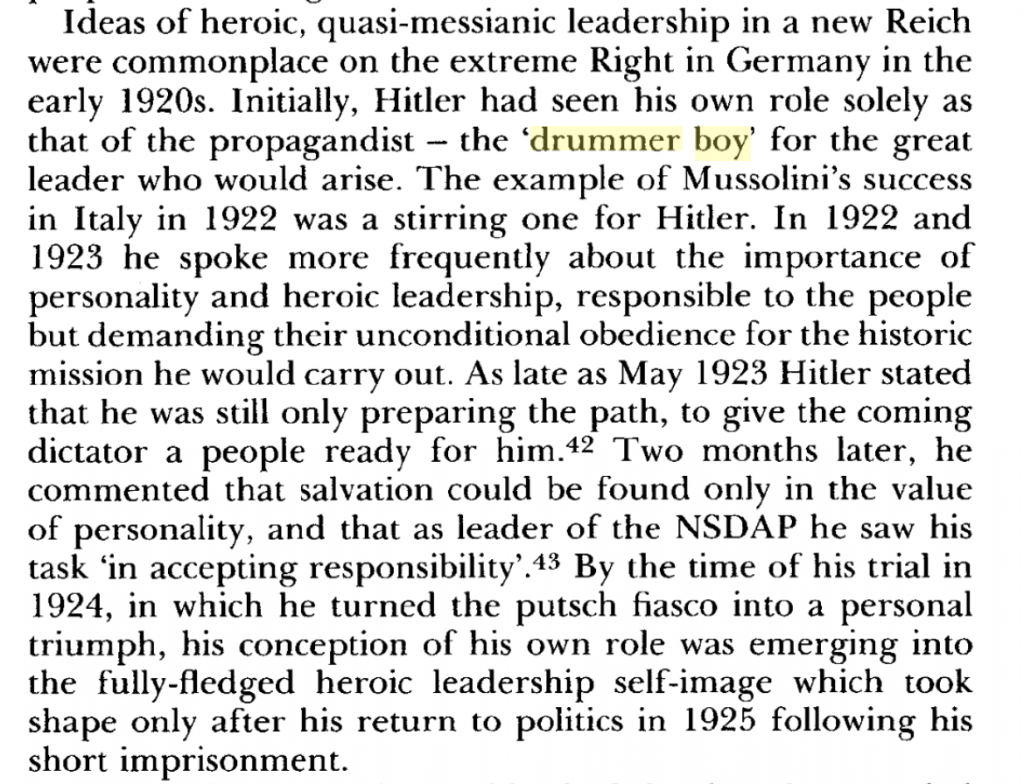

In the 1990s, Ian Kershaw argued that Hitler came to power because of the nature of German society at that time. He argued that Hitler and the Nazis took full advantage of the power ‘handed’ to them in 1933. The propaganda was used to build on the ‘superman’ image of Hitler.

The following extract is taken from Ian Kershaw’s Hitler.

Richard Evans argues that the Nazis did not seize power but won it legally and with consent.

He argues that the use of Article 48 (rule by presidential decree) by Hitler was nothing new to the Weimar Republic. President Ebert had used it 125 times between 1918 and 1925 and Presidents Hindenburg used it, predominantly after 1929. Furthermore, the German parliament ceased to function the more Hindenburg and his Chancellor Brüning used Article 48. Further evidence that Germany had ceased to become a democracy was that the Reichstag met one-hundred days a year from 1920 to 1930, twenty-four days from 1930 to 1932 and only three until February 1933.

Hitler’s Enabling Act bypassed the German constitution and the Reichstag. This was not a new strategy to President Hindenburg and von Papen, they had tried to establish this in 1932 as a way to keep the NSDAP from power. Professor Eberhard Kolb, 1997.

Volker Ullrich argues in ‘Hitler, Ascent‘ that he was a gambler and an actor. At each stage, as leader of the NSDAP, he would gamble all or nothing to achieve power. For example, he was offered the vice-chancellorship of Germany but turned it down, gambling that if he waited for the right opportunity he would get the top position. Furthermore, as an actor, he could be charismatic to an audience if he needed to be or authoritarian when the circumstances required him to be. In this way, he could manipulate others to support or obey him.

J.S. Conway stated that there was no seizure of power by the Nazis in 1933, he was handed it by Hindenburg. But after the Second World War had ended the German people promulgated the theory that they took power, a coup d’etat, to absolve themselves of any guilt. To argue against this is to show the evidence of the Munich Putsch and Hitler’s dismissal of democracy. Moreover, his 25-point plan and the promises contained in Mein Kampf were sufficient to warn the people of his view of leadership.

The following are sections from J.S. Conway’s Machtergreifung or Due Process of History: The Historiography of Hitler’s Rise to Power, 1965.

John Lukacs belongs to the intentionalist school of thought. He accepts that Hitler was helped to power by German society but he had his own plans for the country and made changes as a result.

Student Interpretations

Consolidation and Maintenance of Power

Ian Kershaw explained that Hitler was meant to be seen as the all-powerful, all-knowing leader, who prevailed over a system of total order, but the contrast between image and reality was a stark one. Far from it being a very orderly structure of command, in fact it was very disorganised and rather chaotic. It really is quite a remarkable system, if you can call it a system at all, where there is no collective government but yet where the head of state actually doesn’t spend all his time dictating. He also explained that German society was mostly to blame for Hitler’s maintenance of power. The important organisations and people of the country kept him in power. In fact, Kershaw argues that in a different decade Hitler would not have held power in the country. As a result, he belongs in the structuralist/ functionalist school of thought.

Ian Kershaw sees the Fuhrer as a ‘lazy dictator’ who possessed absolute power but lacked the energy or attention to use it much. Hitler did not work long hours, loathed paperwork and had no interest in overseeing projects in any detail. He was reactive and unable to produce new ideas, relying instead on advisors and acolytes in his inner circle. Alpha

Karl Bracher agreed with Kershaw in that Germany was governed chaotically. This actually helped him rule over his party and the country, there would be no organised resistance. Another functionalist Saul Friedlander, explains that German ‘Wagnerian’ nationalism and endemic anti-semitism enabled Hitler to become the leader and hold onto power within Germany.

Richard Evans argues that Nazi repression, exercised through the Gestapo and concentration camps, was on a small scale and did not affect the majority of the population. The regime was generally popular with the polls and elections being evidence of this. The population was happy to denounce enemies and knew of the existence of concentration camps, acknowledging their usefulness. Moreover, there was no doubt that Germans knew of what was later called the Holocaust. He further argues that there was a consensus after the Second World War that Nazi Germany was a ‘police state’ – this was the ‘intentionalist’ school of thought.

Evans also argues that the purpose of Nazi propaganda was for obedience rather than persuasion.

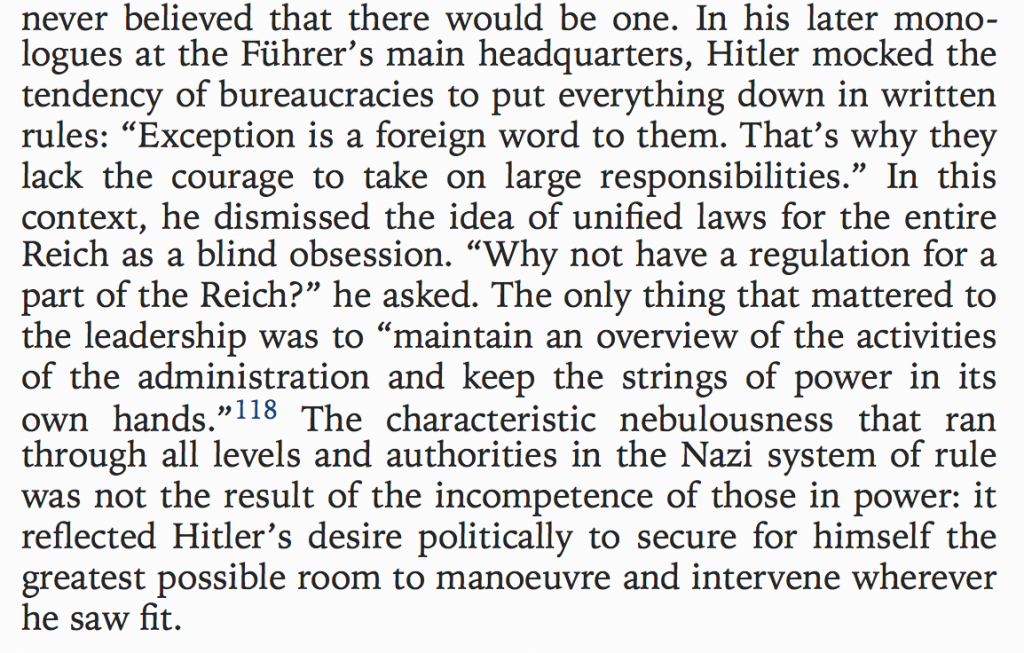

Karl Dietrich Bracher acknowledges the Nazi state was less organised than outward appearances suggest, Bracher believes this was largely due to Hitler, who intentionally created multiple departments and encouraged competing interests. He did this to ‘divide and rule’, enhancing his own power by distracting those who might covet it. Alpha History

Recently, Catherine Epstein argues that,

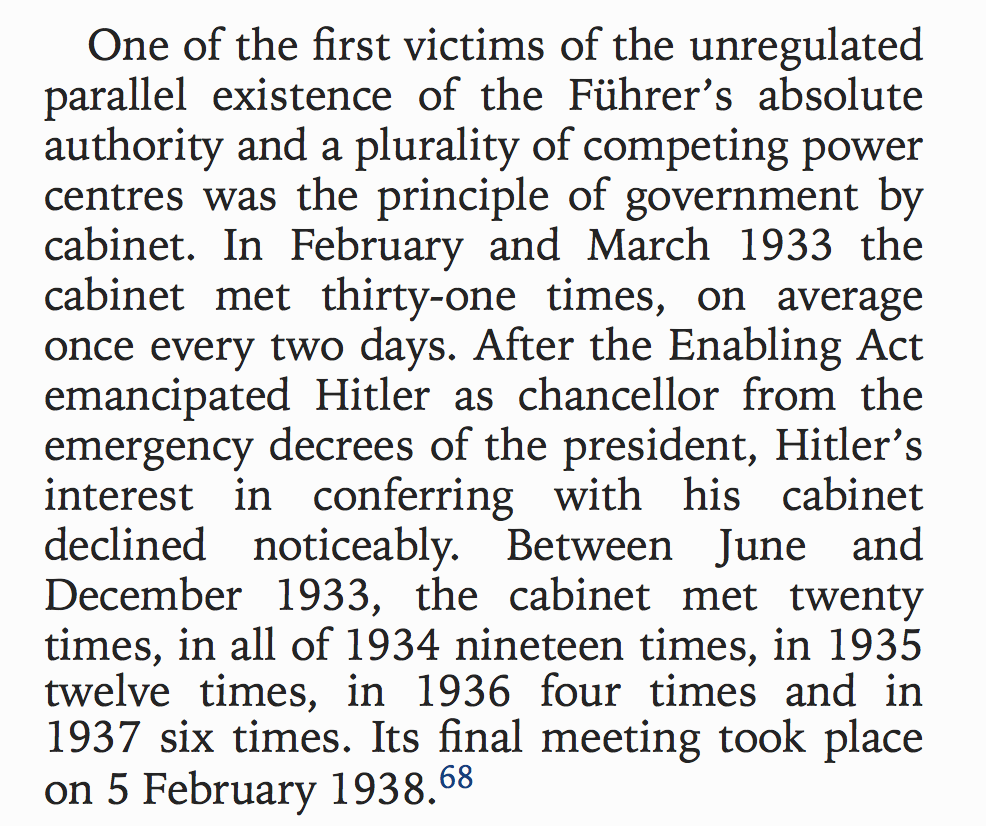

Volker Ullrich explained that Hitler became more authoritarian as the years passed. Ullrich explains that Hitler discussed policy with his cabinet on increasingly fewer occasions between 1933 and 1938.

Hitler did not fully support national state laws so he could have flexibility to intervene when he wanted…

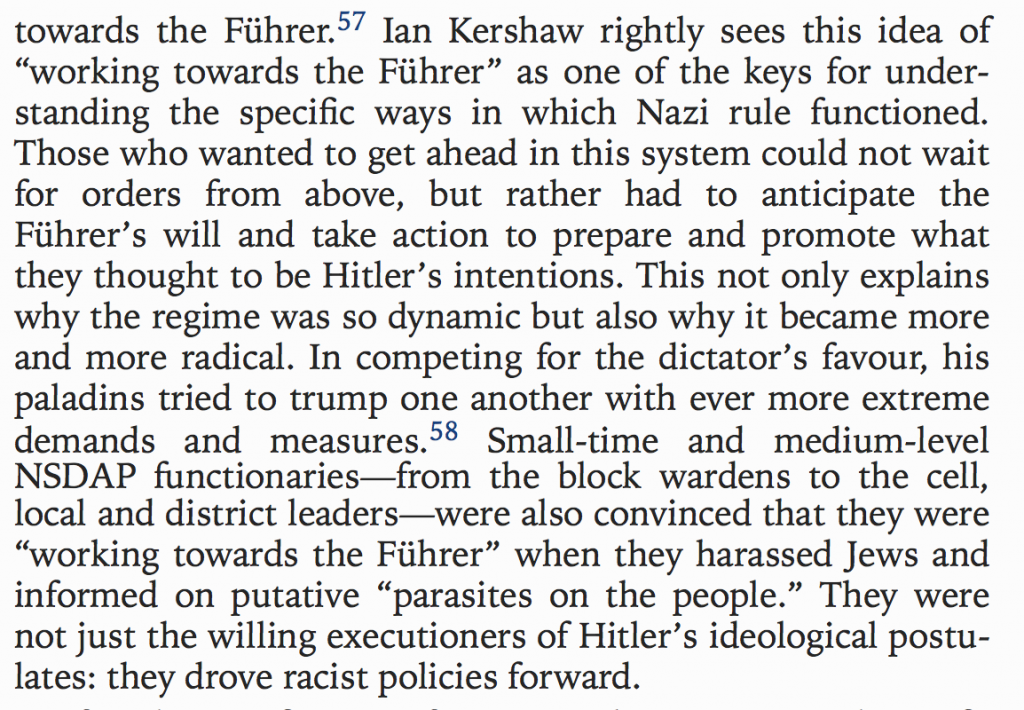

‘Working towards the Fuhrer’ meant that NSDAP members had to anticipate what Hitler wanted.

Ullrich agrees with Ian Kershaw in that the Nazi regime was disorganised, it only gave the impression it was the opposite through propaganda and orderly military parades.

Frank McDonough argues in ‘The Hitler Years’ that Hitler was far from totalitarian.

Aims and Results of Policies