Political Parties of the Weimar Republic

Political Parties of the Weimar Republic

German National People’s Party (DNVP) – Nationalist, initially opposed the Weimar constitution and the new political system. It called for the restoration of the monarchy and an authoritarian government. Supported by the middle and upper classes.

German People’s Party (DVP) – Began as a nationalist, conservative, pro-industrialist and anti-socialist party that was largely dismissive of the Republic. During the 1920s, it became more moderate, establishing good relations with centrist parties. Gustav Stresemann was their leader. Supported by business.

German Democratic Party (DDP) – Largely Protestant, middle-class, often from professional groups of lawyers, doctors and liberal academics. Firmly supportive of the Weimar Republic and resistant to militarism and antisemitism.

Communist Party (KPD) – Its earliest members came from the ranks of the radical Spartacist group. Drawing on a membership of more radical workers and a small group of radical intellectuals, the party was fundamentally opposed to the existence of the Weimar Republic

Catholic Centre Party (Z or Zentrum) – Was more diverse than any of its Weimar rivals. Catholic women voted for the party in very high numbers. The Centre Party was vital to the stability of the Republic, and it was a part of every Weimar government. Its leaders served as chancellors for nine administrations and were included in each of the twenty-one cabinets that ruled during the fourteen years of the Republic. With the change in leadership of the party in 1928, it drifted towards its more conservative wing which had evolved into the Bavarian People’s Party (BVP).

Social Democratic Party (SPD) – The SPD was committed to further reform of Weimar society and hoped to eventually make the institutions and economy of Weimar more egalitarian. Took its support from blue-collar trade union skilled workers, and at times from more progressive white-collar workers and intellectuals. German women from working class families voted for the Social Democratic Party in large numbers.

Bavarian People’s Party (BVP) – The Bavarian section of the Centre Party. More Conservative than its parent party. It was firmly pro-Catholic, anti-socialist and focused on interests specific to Bavaria.

National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP-Nazi) – Initially attracted young men who had been in the military and had not been able to reintegrate themselves into the civilian society and economy. The party also drew support from members of the lower middle class, shopkeepers, artisans and white-collar workers. Opposed to the Weimar Republic and continued to work towards its abolition even when they fought in elections from 1925 onwards.

Political Parties of the Weimar Republic

Political Constitution

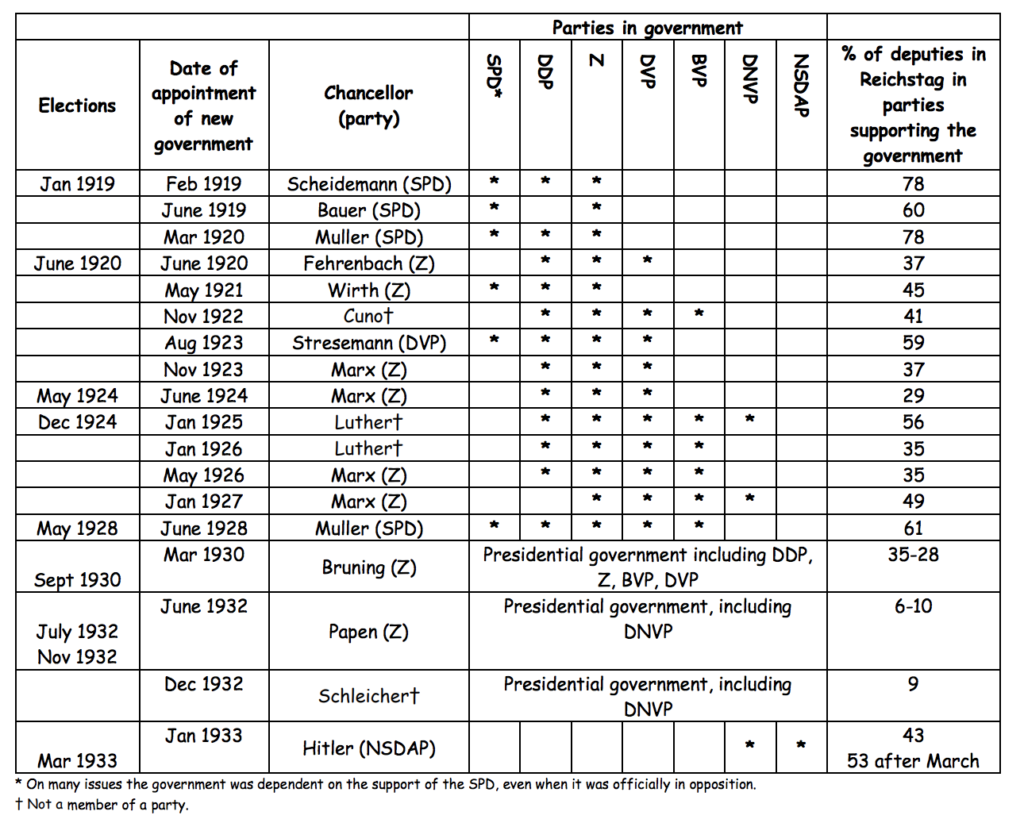

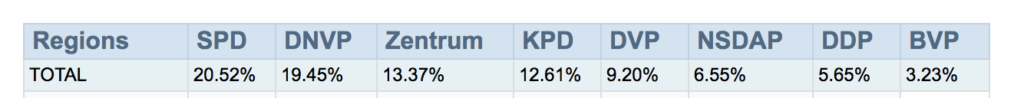

One could argue that the voting system in the Weimar Republic, proportional representation, was to blame for the political instability. Too often, parties which did not agree with the new republic became part of the government. For example, the 1924 elections produced the following results,

The table above shows that the DDP, Zentrum, DVP, BVP and DNVP formed the coalition in January 1925. Two of these parties were hostile to the Weimar Republic, the DVP and DNVP.

However, to counter this argument you can state that both of these parties took part in democratic elections and did not use violent methods to subvert the government or system.

Social and Economic Policies

The Golden Age?

Weimar Republic and Stresemann

Hyperinflation and why Germany never really recovered from WWI

Bruning’s Chancellorship: The Beginning of Authoritarian Rule?

- Bruning arranged the suspension of reparation payments in 1931 as a result of the dire state of the German economy.

- He advocated austerity policies to solve the economic problems although the Reichstag would not pass them so he chose to use Article 48 to do so.

- When the NSDAP and KPD increased their seats in the 1932 election, he found it even more difficult to pass legislation. Article 48 was again the solution.

- In addition to austerity, he attempted to reverse the social and economic policies of previous governments; this would cut back on public expenditure. He also added tax increases and cut the salaries of government workers. This significantly reduced government borrowing.

Why did people who lived during the Weimar Republic begin to vote for Hitler?

- Munich Putsch gave him publicity.

- Played on the fears of nationalists about the Treaty of Versailles, loss of the First World War and the state of the economy.

- Passionate speaker, also entertaining.

- Gave solutions, however practical, to some of people’s problems.

Foreign policy

Historians and Perspectives

Historian Says Weimar Republic Holds Potent Lessons for Today – Eric D. Weitz

Eric D. Weitz, “Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy

Richard Evans argues that a study of democracy is very relevant today. He explains that, according to the UN, the number of countries with strong democracies has decreased in the last few years. He asks is there are any parallels to the Weimar Republic and to what extent people should be concerned.

The Weimar Republic was a change from the Kaiser’s previously autocratic state. His regime was overturned in 1918 by a largely bloodless revolution, blaming it for defeat in the First World War and the problems it caused Germany. The new government was seen as the most democratic in the world at that time. Free elections, voting rights for both men and women, a free judiciary and press, local autonomy for states, etc. And democratic parties won a majority in the elections of 1919. So why did it fail?

Evans explains that the left and right would not work with each other. The two extremes did not believe in the democratic system of government that Germany had. Moreover, the poor state of the economy throughout the 1920s and 1930s continually maintained the opposition to it. Nationalism had not died from pre-war Germany and arguably grew up to as the 1920s ran into the 1930s. There was a belief that a return to better times was a viable option (the Weimar culture emulating the ‘Roaring Twenties’ was seen by conservatives as a step too far). Germany could be ‘great again’.

The nationalists were not united in the 1920s but their policies had similarities. Some advocated war as a solution to the country’s problems, and violence or intimidation were options to stop any opposition. This was carried out by paramilitary forces, the Sturmabteilung or Storm Detachment (SA) was one such group which were loyal to the Nazis. Ironically, Hitler came to power to stop the violence on the streets, much of which the SA had caused.

On the other hand, the Weimar Republic caused its own destruction. One can argue that Proportional Representation was a factor in bringing down the republic, Germany had fifteen different governments in as many years as parties were unable to reach a consensus. They were made up of coalitions and were liable to break down when events made life difficult for the parties. Richard Evans argues that this was not a factor, however. There were too many divisions before 1919 that it would always be difficult to reach consensus: left v right, communist v nationalist, protestant v catholic, wealthy v poor, rural v urban, state v state.

If you are to argue the Weimar Republic was always going to fail, Evans explains that the government had successes as long as the ministers were kept in post for many years. Gustav Stresemann was the foreign minister for nine successive Cabinets, Heinrich Brauns was labour minister for twelve and Otto Gessler was army minister for thirteen. These were all successful ministries.

But the infamous Article 48 was clearly a factor in bringing down the government eventually. The President could rule the country by decree and even if parliament disagreed, he could use Article 25 to dissolve it. The first President, Ebert, used it Article Forty-Eight 138 times when in office. He set a precedent to use it and his successor, Hindenburg, used it regularly during the Depression years. His Chancellor, Bruning, was forced to use it as the Reichstag had no workable majority and was regularly halted because of the violence and theatrics of the Nazis. It got to the stage where the Reichstag hardly met, the president decree used increasingly more.

Yet the 1928 election only gave the Nazis less than 3% of the vote. Without the Depression, the fact that only four years later they were the largest party would never have happened. However, Evans does not put Hitler’s success down to the failure of the Weimar governments to deal with their economic problems. Instead, it was the rise of the communists which drove people from all classes to vote for the NSDAP. As the Nazi vote was declining in 1932, the communists (KDP) was growing. This led to the conservatives appointing Hitler as chancellor.

David T. Murphy argues that German public opinion was generally against all the foreign policy decisions of the Weimar Republic. The reason was that the acceptance of the Treaty of Versailles remained in place despite the amendments made.

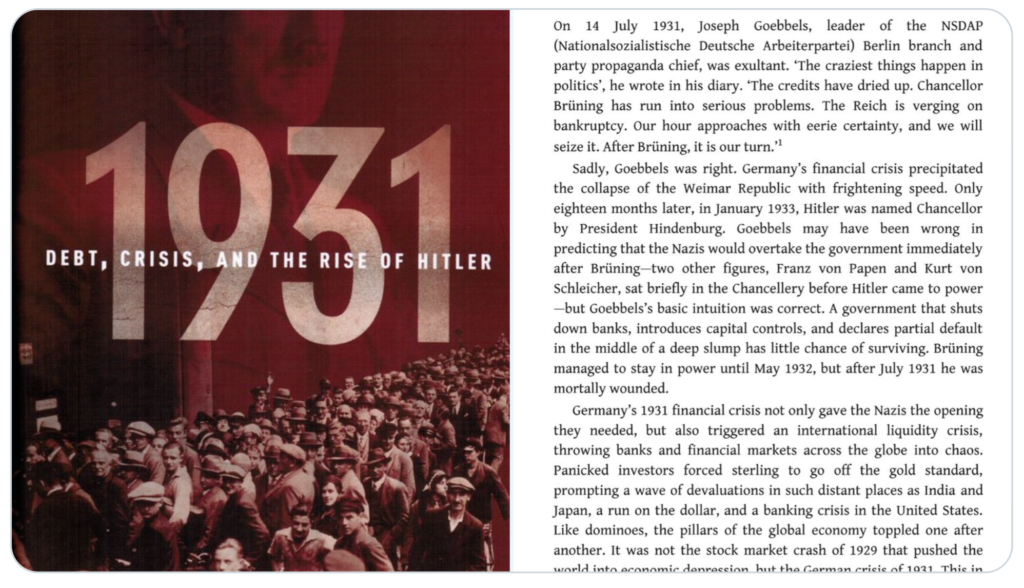

Tobias Straumann explains the following in his book ‘1931’,

Hans Mommsen, in the Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy, writes

Stephen Lee, in The Weimar Republic, writes