Timeline

1958 The Great Leap Forward begins.

1959 Lushan Conference, USSR stops assistance to China for their nuclear programme.

1961 Sino-Soviet split

1962 The Great Leap forward ends. The Socialist Education Movement begins

1964 China’s first nuclear bomb developed.

1966 Cultural Revolution begins

1967 China builds its first hydrogen bomb.

1969 Skirmish with USSR over Zhenbao/ Damansky Island.

1971 Lin Bao dies controversially, after being nominated as Mao’s successor in 1969.

1972 US President Nixon visits Mao in Beijing

1976 Chairman Mao and Zhou Enlai died. The Cultural Revolution ends.

Task – Put these events into a table with the headings Political, Social, Economic and Military.

Great Leap Forward

According to Dikotter, ‘we’ know of 20th-century horrors because Nazi Germany fell (the Holocaust), Stalin died (Purges, Gulags, Holodomor ) and Japan (Rape of Nanjing) lost the Second World War. It is more difficult to find evidence to prove the horror of the Great Leap Forward because the communist party is still in power. He argues that forty-five million died between 1958 to 1962.

Purpose

- The purpose of the ‘Great Leap Forward’, arguably none of these words seemingly fit the event, was to create a huge army of workers for China. Mao wanted the country to overtake Britain in steel production within fifteen years. But as the workers required to produce this had to come from agriculture, the plan was to make food production more efficient. Consequently, villages were to be collectivised, amalgamated to form a larger and more efficient system of production – the communes. This included the land which had been previously given to the peasants in the 1930s and 1940s, was now taken away. Mao was sixty-four years of age by 1958 and wanted to create a lasting legacy before he died. As China had not advanced as much as he had wanted, the Great Leap Forward was the solution to surge past the USSR and other leading nations. No matter than collectivisation failed in the USSR, Mao believed he was cleverer than Stalin and could make it a success.

- Water and the Yangxi

What happened?

- The political representatives of the CCP within the communes had quotas and targets to be met. However, the workers and peasants were fearful of the consequences if these were not met and exaggerated the results. Consequently, the CCP took more of the produce than what was possible and the commune faced food shortages and probably starvation.

- Two to three million people were killed because of the violent methods to force people to work or hand over the food. It was not just the famine that killed so many Chinese people.

- People who could work were fed, those who were too sick, old or suffering through severe lacks of food were not. This is a key point in that famine leads to a lack of food and people starve. However, in China during these four years, food was withheld deliberately. In Mao’s words ‘Revolution is not a dinner party.’

- One of the strategies used by peasants was apathy – they did not do any work if the government representative was not present. This would conserve energy and make them less reliant on what food was available. There were stories of villages sleeping through the winter, a human hibernation.

- Another strategy was because of the basic instinct of survival. People fought each other, peasants attacked cadres (party officials), stole from trains and granaries, and even sold all possessions including their own children. Food was acquired in various ways too, it could be stolen, bought on the black market or even taken from the ground before it is ripe of fully grown. The latter point obviously led to health issues for those who ate it.

- Huge amounts of housing were also destroyed during this time. They were used for fuel, build other things under collectivisation (better villages?) and to prevent peasants hiding resources such as food. Dikotter argues that the Great Leap Forward was the greatest destruction of property in human history, between 30 to 40% of all private homes were destroyed for fuel, food or to make into other products.

- The Great Leap was practical in its vision for China. For example, why preserve the Great Wall of China when its materials could be used to build something new and more useful to modern society. Many historical

- By the time most villagers realised how terrible the situation was, they were too weak to do anything about it. The weak remained in the villages whereas the stronger were able to move to other places in search of food and work. And if they died, there was evidence that cadres hid their dead so that they could deny the famine or the failure of the policy.

- The Great Leap Forward was a project which also aimed to improve the infrastructure of the country. Canals and railways were to be built. Unfortunately, these efforts were insufficient to make collectivisation a success. Forcibly moving resources such as food and machinery to other parts of the country to establish communes relied on infrastructure, the fact that it was poor meant that much-needed food rotted for lack of roads and rail.

- The communist cadres, although in charge of the collectivisation project, were also punished if they were too honest in reporting what was happening in the country. Those senior officials in the party who criticised the policy were purged during the Cultural Revolution.

- There were huge plans to grow forests and improve the supply of trees in the country. Thousands were grown but rarely had time to grow to full size, the famine meant that people needed fuel (especially during the winter) and materials to build so the young trees were pulled down. In total, millions of trees were pulled down, the completely opposite result of what Mao wanted.

- Clearly the death of most sparrows (Mao asked the USSR to replace them!), who ate a variety of insects, had a disastrous impact on the agricultural production. This further added to the manmade famine that was the Great Leap Forward.

- The Office for Water Conservancy was established in 1957 and was responsible to build dams and reservoirs to improve the water supply and consequently agriculture. But mistakes were made with flooding and silt ruining agriculture.

The Lushan Conference

- Lushan Conference

- The Struggle Between Peng Dehuai and Mao Zedong

- Michael Lynch agrees with Dikotter’s analysis, the Lushan conference of 1959 should have been the end for Mao because of the disaster befalling China. However, only Defence Minister Peng Dehuai had the courage to criticise his leadership. A veteran of the Korean War and a member of the Long March, Peng was a tough man who traded insults with the PRC chairman. However, none of the other leaders, Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping and Liu Shaoqi, had no such courage.

- ‘But in one of the great betrayals of modern Chinese history, the self-proclaimed leaders of the people rallied to Mao and turned against Peng.’ (Lynch, p. 173)

- As such ‘…it was now impossible to deal with a famine that officially did not exist. To keep up appearances, grain continued to be exported abroad even from the provinces where the death toll was mounting daily.’ (Lynch, p. 173)

Resistance and Opposition

- The period after Lushan ‘was a study in fraudulence, sycophancy, and terror.’ (Lynch, p. 173) Dikotter agrees in that this prevented any significant opposition to Mao’s policies, who do you turn to when complaining? Any resistance was quickly put down by the regime.

- But there were some examples of resistance. Groups, some in their thousands, robbed trains and granaries. Thousands of tonnes of grain were stolen.

- The state did not punish all of those responsible, assuming they knew who they were, and singled out the ringleaders. Perhaps there were too many to punish?

Propaganda

- Lynch explains that newspapers contained photographs of a plentiful harvest and the success of the Great Leap forward. And, as with all authoritarian leaders, a scapegoat was found for any problems. Mao blamed peasants for hoarding grain supplies and sent them to laogai, the Chinese labour camps, where ten million were incarcerated. One could argue that he learned from Stalin in how to solve this problem, he himself had blamed the kulaks for the failure of collectivisation in the Soviet Union. They were sent to gulags, the Soviet equivalent of laogai.

- You could use the word famine in the CCP ranks, only the ‘natural disasters‘. Dikotter explains that there were some natural disasters during this time but nowhere near enough to destroy the lives of so many people. But it served as a convenient excuse for cause of the huge deaths.

- Mao launched a poetry competition in the summer of 1958 to glorify the bumper harvests.

- 50 000 Party officials met in Shanghai in 1958. They were all fed very well, giving the impression that the harvests were plentiful (this also led to a swelling of Party members as the word spread that they would obtain food). For example, there were 12.5 million members in 1958 and 17.5 million in 1961.

Mao’s Genocide?

Consequences of the Great Leap Forward and Blame

- People left their homes and villages and became refugees. Parts of the country, especially in rural areas became ghost towns. They even tried to leave the country, aiming for Burma, Thailand and the West. But very few foreign powers, even the UN, wanted to help them. Some tried to get to Taiwan but this proved difficult.

- Blame, everybody blamed somebody else. But the phrase ‘If only Mao knew‘ was common, this may explain why he escapes blame even today.

- Education was drastically impacted. Children spent most of their time working rather than studying so the literacy rates were severely affected.

- Parents had to work much more and so this had an adverse impact on the their children, they were not fed adequately or suffered medical problems which may have been prevented with better care.

- The foreign powers ignored the situation in China, even though the information coming out of Taiwan alerted the west. Even future French president visited the country and said that nothing was wrong in China.

- Dikotter argues that the central planning for the Great Leap Forward was a key factor in the lack of food being produced. The CCP hierarchy planned for what they thought people needed, not what they wanted. How can a central government plan for 630 million people? And as their was a hierarchy in the CCP, the best produce went to the ‘best’ people. The Party leadership lived in high-walled villas (so people cannot see into them), with abundant food and chauffeur-driven cars.

- Peng was labelled a rightist and removed from power. He suffered terribly under the Cultural Revolution and died in prison in 1974.

Cultural Revolution

Purpose

- Michael Lynch argued that Mao’s intention during this period was to destroy China’s past. He used Lin Biao as a virtual minister of propaganda to elevate him above ordinary politics.

- Mao saw that Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping had improved Chinese agriculture by allowing peasants to sell their surplus produce. But the return to individual farming meant that his earlier programme, the Great Leap Forward, had failed. Furthermore, the communes were dismantled too. This made them rivals to Mao. The Cultural Revolution would allow him to remove or dispose of them.

- After the failure of the Great Leap Forward, Mao had lost some of his power and influence. Although the CCP was led by the politburo and so power was shared, before the famine he was its leader. To restore this situation, he needed a purge.

How did the Cultural Revolution maintain Mao’s power?

- A key tool for this was Mao’s ‘little red book‘. 740 million of these were distributed between 1964 and 1968, each containing shorts extracts from his writings and speeches. It became a prescribed text for schools and universities and was broadcast to workers to motivate them.

- According to Mao, “The Chinese Red Army is an armed force for carrying out the political tasks of the revolution.” (Lynch, p. 178). Consequently, he made sure each soldier had the ‘little red book’ as their basic training manual. The loyalty of the army was further strengthened and reinforced his power, despite the failure of the Great Leap Forward and his age.

- With regards to Liu Shaoqui, Mao acted vengefully towards him. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1964 so Mao closed down the clinics which would treat him. Then

- The trigger for the Cultural Revolution was the reaction to the play The Dismissal of Hai Rai from Office. Although it was set in the eleventh century, the removal by the emperor of Hai Rai, a government official, was seen by Mao as an allegory of his decision to remove Defence Minister Peng Dehuai. As the writer, Wu Han, had been critical of the Great Leap Forward, Mao forced him to denounce his own play. His friends and supporters were also targeted for undermining Marxist-Leninist-Maoist thought. Unable to cope with the constant persecution, Wu Han killed himself in 1969.

- Mao also overturned the rule, brought by Lui Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, that his cult of personality be removed and the country should be governed by a collective. Both men were removed from office too.

- In 1966, Mao announced the creation of a Central Cultural Revolution Group (CCRG) which would identify and remove bourgeois enemies.

- Within this group, the Gang of Four emerged. Zhang Chunqiao, Yao Wenyuan, Wang Hongwen and Mao’s third wife, Jiang Qing, made up the group. It was based in Shanghai and Mao used this and the CCRG to undermine his rivals in Beijing.

- Jiang used the group to pursue her vendettas against those who may have slighted her in the past (Zhou Enlai, Peng Zhen). She also led the campaign to rewrite China’s cultural history (see below). ‘Her work dominated China during the remaining ten year’s of her husband’s life.’ (Lynch, p. 190)

- She censored all art forms, everything had to go through her before it was sanctioned. All foreign powers works were banned and Chinese history was selectively removed.

- An example of the type of production which Jiang Qing supported is shown below.

Q – How did the actions of Jiang Qing affect the position of Mao in China?

Q – If Mao was rarely seen during the Cultural Revolution, did it mean he had lost power?

- And Wang Hongwen‘s name became associated with terror in Shanghai, responsible for the persecution and death of thousands.

- In 1966, Mao instructed several high-ranking party officials to be arrested and tortured, he claimed there was a plot against him. Zhou Enlai and Liu Shaoqi protested but this only added to Mao’s distrust of them.

- As a result of the ‘plot’, the CCRG became more active. Mao may not give them any specific criteria but he did not limit their powers either.

- Mao’s attacks would involve the youth attacking the old. They had been used before in the 1950s (antis campaigns) and were to be the main instrument of the Cultural Revolution. However, he did not respect them, ‘we must liberate the little devils. We need more monkeys to disrupt the palace.’ (Lynch, p. 184)

- Teachers were targeted by students and were encouraged to do so by Mao. These students would form the Red Guards. The attacks on the teachers went against the Confucianist view of respect for elders. It was part of Mao’s plot to continue the revolution (borrowing Trotsky’s view of a permanent revolution) and remove the ‘Four Olds‘ – Old Culture, Old Customs, Old Habits, and Old Ideas (CHIC).

- This went against the Chinese Confucianist culture, respect was elders was ignored. No matter how venerable, all people became possible targets. Even the most ancient and respected artefacts were destroyed too.

- Deng Xiaoping, Liu Shaoqi and Zhou Enlai all tried to limit this destruction and terror but this only led to their demotion in the party hierarchy.

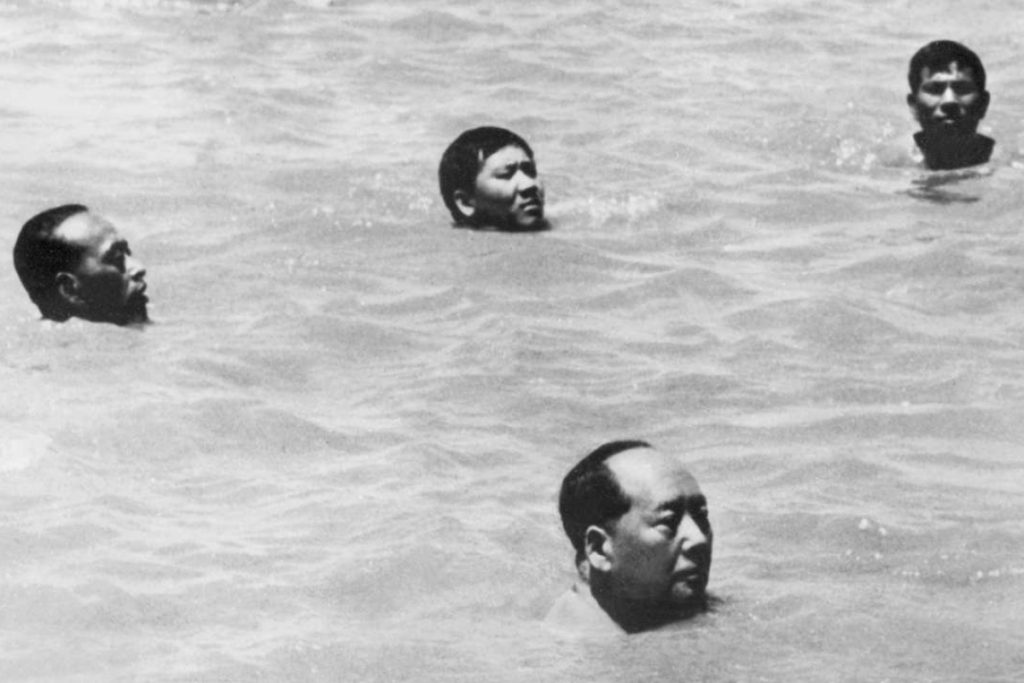

- In July 1966, Mao took his famous swim in the Yangxi River. All the media took an interest and conveyed it to the people. It was symbolic that in China’s greatest river, Mao represented a life force. Mao may have been seventy-three but the swim energised his supporters.

- CCP members were also targeted by Mao, after Liu Shaoqui did so earlier in the decade. A Red Guard demonstration criticised both Deng and Liu. The latter was tortured and forced to ‘admit’ his crimes. Consequently, he was imprisoned and died emaciated in 1969. For Deng, his son was thrown out of an upstairs window, which left him permanently paralysed, and he was eventually exiled to Jiangxi for corrective labour.

- Mao was concerned about coups and plots so removed himself from Beijing for long periods. When returning, he moved from place to place to avoid any recriminations for his actions. He even gave up his personal preference for young peasant women in case he was poisoned.

- However, Lynch argues that even though Mao was absent he was still in control. ‘Everything was done in his name‘. (Lynch, p. 188)

- Dikotter argues that during the Cultural Revolution there were the Red Years of 1966-68, when the Red Guards look for their teachers and the intelligentsia and the Black Years of 1968-1971, when the army takes over. It looks for potential rivals and the educated. Millions are ‘re-educated’ by sending them to the countryside. After Lin Bao dies (in a questionable plane crash) the Grey Years set in, the army no longer in charge.

- Mao changed his view of the Cultural Revolution when China’s workers stopped working. Teachers were one thing, workers, and China’s economy was different. So he brought in the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) to take over the role of the Red Guards. The latter was ordered to go to rural areas to farm, ‘to go up to the mountains and down to the villages‘. (Lynch, p. 188)

- This allowed Mao to get rid of the ill-disciplined youth with thirteen million of them going into the countryside. After Mao’s death, those who spoke about their experiences felt that they were used. Consequently, they worked even harder for material gain after 1976.

- Two million PLA soldiers supported Mao, showing that he still had the loyalty of the army.

- Mongolia: 800 000, largely Mongols arrested and questioned. Many were tortured and even killed.

- People began to leave the collectives in the 1970s. This gathered sufficient momentum and was too big to turn around by the 1980s. Economically the people changed but politically they did not, resulting in the failed demonstrations in Tiananmen Square of 1989.

Summary of Frank Dikotter

In Our Time: The Cultural Revolution

Propaganda and the Cultural Revolution

Memories of the Cultural Revolution

Jiang Qing and ‘her’ Cultural Revolution

Legacy of the Cultural Revolution

Watch the following up to 06:35.

A. How did some of the youths of China react to the Cultural Revolution?

B. How did the Revolution influence Chinese leaders today? Would they want a repeat of it?

Podcasts

Mao’s Cultural Revolution: everything you wanted to know

173. Chairman Mao & the Cultural Revolution

Cult of Personality

Frank Dikotter

- A further strategy to reinforce the cult of personality was the Great Leap Forward (see above). The disastrous policy could have ended him as the ruler of China. He was saved in that Lin Biao called it a great accomplishment and Zhou Enlai demonstrated his loyalty by taking the blame for many of the policy’s failures.

- Mao’s ‘Quotations of Chairman Mao’, also known as the ‘Little Red Book‘ was carried by all soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army. This ensured he had support from within the military.

- He tried to reassert his power and cult of personality again with the Cultural Revolution (see below). He targetted those who ‘discussed’ the Great Leap Forward, people who spoke out during the Hundred Flowers Campaign and encouraged students and the young (who all had years of CCP education behind them) to eliminate any evidence of the old culture, even if this included people. The young Chinese showed huge devotion to their leader and destroyed temples, churches, shops, books, in honour of him. During this time, people tried to outdo each other in showing their loyalty to Mao. Badges, posters, pictures, and books were made in their millions. The demand outweighed the supply and this led to other industries suffering – aluminium became in such short supply that Mao had to put a stop to the badge craze.

- In 1968, Lin Biao launched the Three Loyalties and Four Boundless Loves. It took Mao’s devotion to new heights, all offices, school, and factories had an altar with Mao’s picture in each. The Chinese people would see him every day, bowing as they did so. Busts and statues were also made, 600 000 in Shanghai alone.

- However, Richard Walker explains that to help create this image of Mao, stories of the Long March focused only on his exploits and heroism, omitting the names of those purged or who were rivals.

- The PLA was used to implement the Cultural Revolution. However, it also made Lin Biao, its leader, very powerful. So after he died in a mysterious plane crash, the power of the army was curtailed, even purged.

Richard L. Walker

- “…It is possible to count the stars in the highest heavens, but it is impossible to count your contributions to mankind.” Peking Radio, 6 December 1967

- By 1972, it was almost impossible to find any area where Mao was criticised.

- The cult of the great leader, great teacher and great supreme commander obscured the real Mao. Even American historians referred to him as Chairman Mao, whereas their own president called just be called Nixon. Only after his death did some in the West begin to question his rule, similar to Stalin in the 1950s.

- In 1958, the People’s Daily wrote “Chairman Mao is a great prophet. Through scientific Marxism-Leninism, he can see the future. Each prophecy of Chairman Mao has become a reality. It was so in the past; it is so today.” (Walker, p. 164)

- Even failures were blamed on others. The best example was Great Leap Forward with Liu Shaoqui and others being blamed for the policy failure. Lin Biao was also held responsible for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

- Walker argues that Mao created an environment where people focused on the ongoing revolution rather than any of his mistakes. Tourists were ‘guided’ around the country so would only see the positives of the revolution…just as in North Korea today.

- He also made sure there was no discussion of a successor, ‘Under Mao there have been no regularized methods for appointment, succession, or government organization beyond the will of the leader.’ (Walker, p. 165)

- Mao could have been a ‘superman’ had he retired earlier than he did. Much like Hitler if he had done so in the late 1930s.

Mao as Superman, by Richard L. Walker

Dealing with Opposition

Mao used both force and persuasion in dealing with any opposition to his rule. You will have read about Force, Land Reform and the Antis Campaigns, Hundred Flowers and Anti-Rightist Campaigns in the consolidation of power. You should add how propaganda and censorship was used too. Importantly, you should identify who the opposition were, why they were targeted and how they were dealt with.

Force was also used during the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. But a dictator cannot rely on fear alone to rule, they need to be respected or even loved. Mao used persuasion via the Cult of Personality and indoctrinated the population with the emphasis on Mao Zedong Thought.